“How many fingers am I holding up?” Winston Smith, the protagonist of 1984, answers based on what his eyes tell him: there are four. Only the Party agent directing his re-education insists that there are five. By dint of electric shocks and various forms of torture, he begins to doubt his own perception, until at the end of the book he also perceives them: there are five, no doubt about it. This passage from George Orwell’s great dystopian novel, in which truth yields to the pressure of power, gives rise to the new documentary by Raoul Peck, 71, Orwell: 2+2 = 5, presented in the Cannes Première section of the film festival.

That scene is the symbol that Peck has chosen to describe a society in which Orwell’s theses are no longer predictions of the future, but pure reality. His vision — based on concepts such as Big Brother, newspeak, doublethink, or thoughtcrime — crosses a present marked by constant surveillance, social fear, and the crumbling of the notion of truth. Narrated by actor Damian Lewis, the documentary interweaves Orwell’s texts and letters with archival photographs, fragments of the film adaptations of 1984 (one made 1956, with Edmund O’Brien, and another in 1984, with John Hurt), scenes from other films, from Oliver Twist to Notting Hill (!), and images taken from television and social networks.

For Orwell, every project began with a sense of injustice that he wanted to confront. For Peck, it’s no different. From his first short film, about Cuban troubadour Carlos Puebla’s visit to Cold War Berlin, to his films about James Baldwin (I Am Not Your Negro) or South African photographer Ernest Cole, which premiered at Cannes last year, his cinema has followed a clear and consistent political line.

“I come from Haiti. From very early on, I saw the hypocrisies of those who proclaim themselves defenders of democracy. And I am a Black person: I was confronted with societies that had decided that I had no right to exist,” says Peck on a terrace overlooking the port of Cannes.

Director Raoul Peck (l) and Damian Lewis attend the photocall for 'Orwell : 2+2Cine, Francia

CLEMENS BILAN (EFE)

Director Raoul Peck (l) and Damian Lewis attend the photocall for 'Orwell : 2+2Cine, Francia

CLEMENS BILAN (EFE)Peck, who grew up under several liberticidal regimes — that of François Duvalier in Haiti, and that of Mobutu Sese Seko during his exile in Zaire — and saw his father imprisoned as an opponent, understood from an early age the importance of speaking out when everyone else is silent.

“As Orwell said: hope, if it exists, has to be built. It does not appear on its own. In the history of humanity, that has never worked. You resist, you organize, you make it happen. Authoritarian regimes, because they lose a war or a revolution breaks out. It may take five years or 30, but the same thing always happens: the system collapses or the citizens resist.”

In that sense, his film seems like a call to action. “It’s not my role, but I want every citizen to ask themselves: what am I doing in this world? At least, those who have the privilege to ask themselves that question. A child born in southern Congo, working in a mine so you can have an iPhone, doesn’t have that choice. But maybe you do...”

More than an ordinary biography, the documentary recalls Orwell in the last years of his life. Sick with tuberculosis and isolated on a remote farm on the Scottish island of Jura, he was determined to finish 1984 before it was too late. His literary testament was published in 1949, just six months before his death.

Peck takes as his starting point the famous Party slogan that structures the novel: “War is peace. Freedom is slavery. Ignorance is strength.” And he makes it the instrument for examining how fascism threatens to make a comeback around the world. Through his images parade Putin, Netanyahu, Milei and Meloni, although the great protagonist is Donald Trump, of course, and his systematic disregard for the truth.

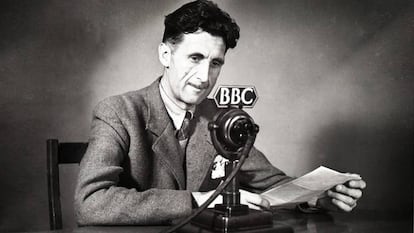

George Orwell.

George Orwell.Orwell was well-acquainted with the mechanisms of oppression. He observed them in Europe, fighting with the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War, but he also exercised them: he was born in colonial India, son of a British official of the Opium Department, and worked for five years as an officer of the Imperial Police in Burma. Both experiences awakened in the writer a visceral rejection of authoritarianism and a deep sense of guilt.

He once wrote that, without the Empire, Britain would be no more than “a cold and unimportant little island where we should all have to work very hard and live mainly on herrings and potatoes,” another observation that already bordered on prophecy.

“One of the things that brought me closest to Orwell when I started reading him was the feeling that he seemed like someone from the Third World, like me. He seemed close to me, someone who understood me, like a brother,” says Peck, politicized in the left-wing circles of 1970s Berlin. “I arrived there when I was 16 and discovered a world dominated by resistance. The city was a political hotbed. My generation was studying in Europe to return home, fight and, if necessary, die. It was not about having a career, a house, or a car. That was not our model. We were fighting to end authoritarianism.” Is that what he continues to do today, through his films? “Unfortunately, yes.”

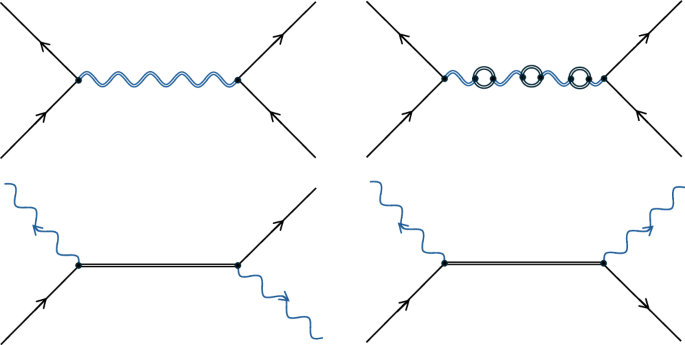

Una imagen del documental, que define la neolengua como "el lenguaje usado para alterar la realidad y manipularlo".

Una imagen del documental, que define la neolengua como "el lenguaje usado para alterar la realidad y manipularlo".One of the most fascinating parts of the documentary is dedicated to newspeak, that language designed to limit critical thinking through euphemisms and prefabricated phrases.

“It is as if every year new words are added to the great dictionary of newspeak. New words, yes, but they always serve the same function: to keep people from facing reality.”

In the documentary, Peck lists a long series of recent examples, such as “special military operation” (war), “legal use of force” (police violence), “cuts” (reduction of social programs) or “tax optimization” (tax evasion). And an even more controversial one: “antisemitism,” used to “delegitimize any criticism of the military actions of the State of Israel,” as Peck puts it, a denunciation greeted with applause at the film’s Cannes premiere. “I’m not saying that antisemitism doesn’t exist, but that’s another thing. And no one should accuse me of being I’m ambiguous. Most of my films have talked about the Holocaust,” he says.

For the director, are the oppressed always right, as Orwell argued? “Fundamentally, yes. But that doesn’t mean I endorse all methods. For example, I don’t support Hamas and its policies. I support resistance, because it’s one people occupied by another, but not that way of fighting,” Peck clarifies.

For him, terrorism does not come out of nowhere: it appears when other ways have failed. “Nobody is born with a suicide vest. When you take everything away from a human being — his identity, his dignity, the possibility of survival — you turn him into an animal. That’s what the Nazis did with the Jews: they turned them into insects or rats. To despise a people in this way is to manufacture the terrorists of the future. And that is what is going to happen in Gaza. There are thousands of children growing up in hell. If they survive, what are they going to become?”

And suddenly, two plus two becomes four.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

.png)