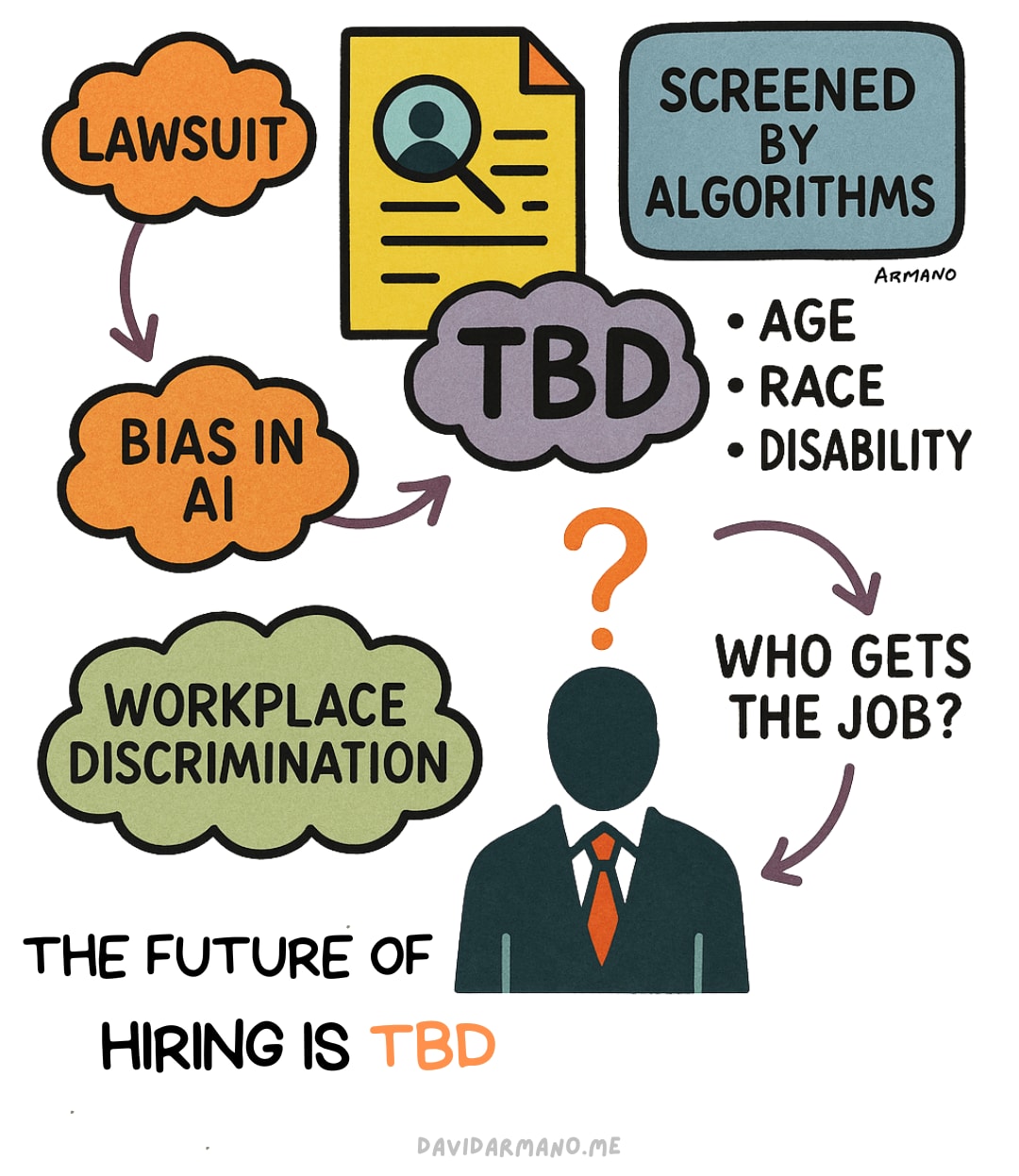

Let’s talk about Workday. Not the software. Not your Tuesday 10 am check-in. I mean the lawsuit. The one quietly reshaping how we think about the role of AI in hiring—and why the future of work, especially the future of getting work, is increasingly TBD.

In 2023, a man named Derek Mobley sued Workday. He applied to more than 100 jobs using their platform and claims he was denied across the board—not because of his skills, but because of his age, race, and mental health history. He’s Black, over 40, and lives with anxiety and depression. That trifecta, he alleges, became a digital red flag. One that Workday’s AI, acting behind the scenes, picked up and quietly sorted him into a digital no-go pile.

That’s not a small allegation. It’s a shot across the bow of the HR tech industry.

Workday fired back with a now-familiar line: “We don’t make hiring decisions. Our clients do.” But here’s where things get interesting. A federal judge ruled that Mobley could proceed under a theory that Workday—though not the employer—acted as an “agent” of the companies doing the hiring. That one decision cracked open a new kind of liability. One where software providers, not just the employers using them, could be held accountable for discrimination baked into algorithmic systems. In May 2025, the court gave preliminary approval for a nationwide collective action. If you’re over 40 and you applied to a job through Workday’s platform since September 2020 and didn’t get it, you might be part of this class. The focus? Age discrimination. The theory? That AI designed to “optimize” hiring decisions was replicating the same old human biases, just faster and with better UX.

Amanda Goodall, a workplace/jobs content creator who goes by “The Job Chick,” puts it this way:

“He claims their algorithm systematically filtered out older applicants. Now it’s a collective action, and the court just expanded the scope big time.

Think about that for a second. It means the tech stack behind the hiring process isn’t just a tool—it’s a participant—one with potential legal exposure.

And this is where the plot thickens.”

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: we’re entering a world where you might never meet your screener… no phone call. No email. No rejection letter. Just an algorithm quietly deciding you’re not the right fit. Not today. Not ever.

This Isn’t Sci-Fi. It’s the Current State of Seeking Work Today.

Hiring software used to be a sorting tool—now it’s a decision-maker. And the decisions are getting harder to audit, easier to automate, and far more consequential. You might never know why you didn’t get the job. You’ll see that you didn’t. And that silence? That’s the sound of AI doing its job a little too well.

Workday isn’t alone. This is about a system-level shift. As AI becomes embedded into everything from resume parsing to personality assessment, we have to ask ourselves: what happens when the machines take the first crack at evaluating our humanity?

Why This Lawsuit Matters (Even If You’re Not Job Hunting)

Mobley’s case is a warning shot. Not just to Workday, but to the entire HR tech industrial complex. If AI vendors can be held liable under civil rights law, everything changes: product design, legal contracts, data transparency, risk assessments.

It also sends a message to employers. You can’t just plug in a black-box algorithm and hope for the best. The days of plausible deniability are numbered (potentially).

But let’s zoom out.

We’ve moved from The Great Resignation to The Great Termination and, now, to The Great TBDfication of work. Hybrid work is table stakes. Loyalty feels optional. AI is automating tasks once considered too nuanced for machines. And trust—the glue between employers and employees—is fraying at the edges. I often talk about my GenX peers who are struggling to find work, and the desperation in their voices when they talk about how challenging it is to go up against the algorithms is palpable. But it’s not only GeX feeling career frustration when it comes to job searches. From Fortune:

“Gen Z is increasingly burned out from job hunting before even getting started. Frustrated applicants have lamented on TikTok about the number of rejection emails they have received from companies and expressed fears that the job market feels broken. And recent data backs them up: Entry-level job postings in the U.S. overall dwindled by about 35% since January 2023, and roles that are easily automated by AI are experiencing a disproportionately large impact.”

What Comes Next?

Regulators are circling. Legal frameworks are catching up. Vendors are getting nervous. And workers—especially the most vulnerable—are left wondering if the deck is quietly being reshuffled without their consent.

We can’t code our way out of bias. But we can design systems with accountability, transparency, and feedback loops built in. That means better training data. Auditable models. Human oversight. And maybe, just maybe, slowing down long enough to ask: who gets left behind when we optimize for efficiency?

The future of hiring isn’t entirely written. It’s still to be determined. But if this case tells us anything, it’s that the algorithms are no longer invisible. And neither are their consequences.

Visually yours,

.png)

![Linus Torvalds Speaks on the Rust and C Linux Divide [video]](https://www.youtube.com/img/desktop/supported_browsers/chrome.png)