Hi everybody —

Before I launch into this week’s topic, an announcement — I’m going to change the format of this newsletter a bit.

But first, since I’m a historian, let me situate these changes in their proper context (and provide a little state-of-the-newsletter update)!

A little over two years ago, this newsletter went from being an intermittent plaything to a proper weekly publication. Since then, I have published weekly Sunday posts and the occasional midweek bonus edition. I’ve been lucky enough to pick up almost 2,000 subscribers along the way, and I am enormously grateful to those of you who read these newsletters. It’s a lot of fun to learn about history alongside all of you!

I’m going to try a slightly different approach that I think will be more interesting for you and more rewarding for me. I plan to continue posting regularly on Sundays, but, instead of jumping around from topic to topic every week, I’d like to do series of posts, maybe 5 or 6 in a row, that orbit around the same subject. This will allow me to do more reading and dig into these topics a little more deeply. I hope you’ll find them more rewarding to read, as well.

This will also, I think, solve some issues I’ve been having as I try to do this newsletter on top of a day job and other writing projects. This is the writing project that I find most enjoyable, but it’s also the one that takes up the most time and effort (and, if I’m honest, it’s the least financially remunerative one). So I’m looking for ways to streamline my workflow while giving you all something great to read. It’s hard to find a new, interesting historical topic, research it, find a bunch of legal-to-use images to illustrate it, and then put it all together every single week. I’ve spent a lot of time going down blind alleys only to realize that I won’t be able to find what I need to turn a subject into a publishable post. Hopefully, publishing in series will help me to spend more time writing interesting stuff and less time pursuing dead ends.

I still plan to send out occasional midweek posts when the spirit moves me, which may or may not have anything to do with the theme of the series. I also plan to take a week off after each series so that I don’t burn out (I may run a repeat newsletter on these off weeks).

So that’s the plan: more focused series of 6 or so Sunday posts, with a week off in between series. I hope this will prove more interesting for you and more sustainable for me.

So let’s start the first series, which will focus on a place that’s always fascinated me: the American West, where the collision between technology, commerce, science, and nature shaped America’s understanding of itself.

Asbury Harpending had a life that was exactly as colorful as you’d expect of somebody with a name that good. Born in Kentucky, Harpending made his way west in the aftermath of the gold rush. He went to Mexico and struck it rich as a mine speculator there. He was at the center of a secessionist movement that wanted to split California from the Union so that it could join the Confederacy. He armed a schooner and tried to hijack gold shipments. A jury convicted him of treason after only four minutes of deliberation, but he got his freedom in a postwar amnesty. All this before he was 30 years old.

Undaunted by his failures and brushes with disrepute, Harpending quickly made a second fortune through real estate speculation. He became so central to the economy of a booming San Francisco that he staved off a panic by moving a million dollars in gold to the Bank of California.

And then this inveterate hustler got hustled. He met Philip Arnold and John Slack, two fellow Kentuckians who had, like him, made a fortune in the west. These men convinced Harpending and other prominent men — Charles Tiffany, George McClellan, and Nathan Rothschild among them — to buy into their mine in Colorado, where they claimed to have unearthed a stunning deposit of diamonds and other gems. It looked like these American finds might rival the new, impossibly rich South African mines at Kimberley.

Unfortunately, it was too good to be true. Arnold and Slack had purchased gems from South Africa and claimed that they were from “Diamond Peak” in Colorado. When potential investors came to check the site out, Arnold and Slack had scattered and buried these valuables around the mountainside to give the appearance that the earth was full of gems. Slack and Arnold collected millions of dollars in today’s money for mining rights at their fictitious mine.

And they might have gotten away with it had it not been for Clarence King. King found himself on a train with some diamond-hunters who were bragging about the deposits that were going to make them rich. But, unlike the colorful speculators who had thus far invested in the mine, King was a hard-nosed man of science. He thought that the men’s claims were too good to be true and set out to find the truth. He undertook the arduous journey to the site and realized that he could only find gems in disturbed earth, and that the gems appeared in suspiciously consistent quantities. It was a hoax, and when King publicized his findings, the new mining company collapsed.

Arnold and Slack had long since disappeared, which meant that investors like Harpending were left to clean up the mess. He denied that he had been the “master mind” of the plot, writing that

The losses growing out of the diamond fraud fell on the shoulders of the original dupes—W. C. Ralston, William M. Lent, George Dodge and myself….

At last public opinion seemed to settle down to a conviction that the guiding—“the master mind”—was mine.

There was not an atom of valid evidence on which to raise the accusation. On this side of the Atlantic it was never remotely charged in any responsible paper, to my knowledge. The conclusion seemed to be reached very much because of the largeness of my business undertakings and my well-known spirit of venture in commercial lines. Therefore, not a few assumed that because I was always willing to take what might be called by some a long chance, therefore, I must have been the power behind the scenes with Arnold and Slack.

Not arguing the case, this conclusion had to put aside many well known facts, as I said before. I was a man of large wealth, making money as rapidly as was good for anyone, so that the financial inducement was not there. I was young, only 32, had a family of which I was proud, had the best possible standing with business men, both in San Francisco and abroad. Honor bright, does it not seem incredible that a man situated like myself, full of ambition and with everything to live for, would have engaged in an ignoble plot to fleece his friends and the public, a plot absolutely certain to drag him and all belonging to him through the dust?

Asbury Harpending would file a libel lawsuit and disappear from the public eye, becoming a Kentucky gentleman farmer for a while (although he couldn’t stay away from the action for long — he moved to New York and made and lost another fortune on Wall Street before he died).

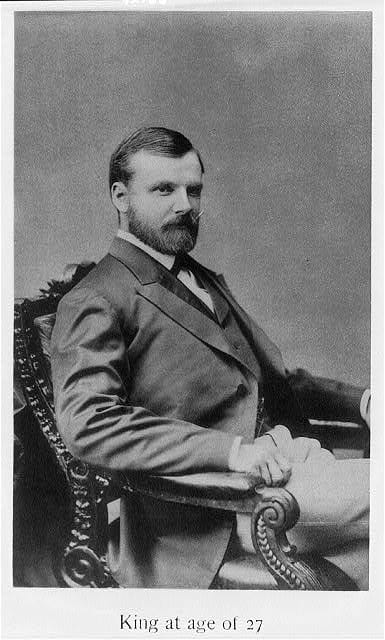

As colorful as Asbury Harpending was, the real hero of the story of the Great Diamond Hoax was Clarence King. And though he may have had a much less manic life than Harpending, he made a lasting and positive impact on the world. King became, in time, one of the country’s great nature writers and geologists, hobnobbing with luminaries like Henry James.

But King got his start as a part of one of the great American adventures. Raised in relative privilege in Rhode Island and Connecticut, at Yale he encountered the eminent geologist and explorer James Dana and became enamored of the nature writer John Ruskin. As soon as he could after graduation, he headed west. While many men his age fought and died in the Civil War, King explored the Sierras in California and helped to survey the future Yosemite National Park. Here he is (on the right) with some of his companions in 1864:

King then returned east and tried to persuade the government to put him in charge (at age 25!) of an ambitious expedition across the west. He and his companions — he hired several other young scientists and photographers — would travel along the Fortieth Parallel, publishing volumes about the animals, plants, rocks, and fossils of this part of the country.

King wasn’t alone in his ambitions. His was the first of the “Four Great Surveys of the West.” King explored northern California, northern Nevada, northern Utah, and parts of Colorado and Wyoming. Soon after, George Wheeler would head out to areas south of King’s territory, Ferdinand Hayden would tackle Nebraska and Wyoming, and John Wesley Powell would travel down the Colorado River.

King’s expedition left in 1867, and came back with eight volumes’ worth of important scientific data and some fascinating pictures. Here’s King and some companions in camp in 1868, near Salt Lake City:

The photos capture, in stark sepia and black and white, the rugged beauty of the country out west. They traveled to Little Cottonwood Canyon in the Wasatch Mountains:

The canyons along the Green River:

And the same river, captured from on high:

Magnificent outcroppings of rock:

And serene lakes:

It wasn’t all wilderness; they sometimes ran into people making a living off of the land:

It was at the end of the survey that King’s skill at reading landscapes allowed him to debunk the diamond hoax; this, more than his scientific work, made him famous. He went on to write several well-regarded works on geology and became the first director of the U.S. Geological Survey. He enjoyed high society in Washington and New York, and after his government service he tried his hand, with middling success, at investing in mining ventures.

You might think that this is where King’s story fades into pleasant-but-boring territory, but you’d be wrong.

At some point in the 1880s, he met Ada Copeland, who would become the love of his life. But she didn’t know him as Clarence King; she knew him as James Todd. Though Clarence King was white (with blue eyes, no less), as James Todd, he claimed to be a black Pullman porter born in the West Indies. He did so because Ada herself was a black woman who had been born into slavery, and a relationship across racial lines seemed impossible.

King and Copeland eventually got married, and he built a double life for himself. He established a household in Brooklyn with Ada, living as a black man. The couple had five children. But using his “job” as a railroad porter as the reason that he was absent from home for long stretches, traveling on geological expeditions or rubbing elbows at the Century Club with the rich and famous.

Though his marriage seemed happy, a double life was expensive; in order to maintain two lavish households, he went deep into debt, borrowing money from banks and wealthy friends.

King didn’t live to an old age; he became sickly in his 50s, and eventually died of tuberculosis while on a trip to Arizona. On his deathbed, he confessed to Ada that he had been married for 13 years to a famous white scientist named Clarence King. She apparently had no idea.

For her part, Ada would outlive her husband by more than 60 years. She died at 103, one of the last living former slaves in America, just a couple of months before the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

What should we make of the intertwining lives of Asbury Harpending and Clarence King? They certainly weren’t dull, and in many ways they illustrated truths about America — and especially the West — in the late 19th century.

The West was a land of opportunity where enterprising men could enrich (and impoverish) themselves with alarming speed. This meant it was also full of scams and speculation, and the hoax that fooled Harpending is a perfect example of the spirit of the age. King’s scientific exploits represent one of the most noble pursuits of the period, the quest to understand nature systematically. But these expeditions were undertaken with the sense that, by understanding nature, Americans could dominate it in some way. And King’s personal life was tangled up in the country’s pathologies over race; he was unable to bridge his personal and professional lives because white Americans were unwilling to value their black countrymen.

It’s hard to think of people whose lives illustrate 19th-century America quite so much as those of Asbury Harpending and Clarence King. Their stories are a characteristically Western mix of science, speculation, and exploitation — all in the service of American mythmaking.

This newsletter is free to all, but I count on the kindness of readers to keep it going. If you enjoyed reading this week’s edition, there are three ways to support my work:

You can subscribe as a free or paying member:

You can share the newsletter with others:

Share Looking Through the Past

You can “buy me a coffee” by sending me a one-time or recurring payment:

Thanks for reading!

.png)