Hydrogen Cars Are Doomed To Fail (And Tech Bros Keep Falling For It)

Hydrogen fuel cell vehicles have been the "next big thing" in clean transportation for nearly three decades. Like nuclear fusion or flying cars, they remain perpetually five years away from mainstream adoption while quietly burning through billions in investment capital.

The fundamental problem isn't technological - it's physics and economics. When examined through the lens of energy efficiency, infrastructure requirements, and real-world performance, hydrogen-powered cars reveal themselves as a dead-end technology that continues to seduce optimistic technologists against all evidence.

The hydrogen dream persists because it offers something electric vehicles don't - the illusion of maintaining our gasoline car experience. Fill up in minutes! Similar range! No battery degradation! These surface-level comforts mask an inconvenient truth: hydrogen is perhaps the least efficient, most infrastructure-intensive way to power a clean vehicle ever conceived.

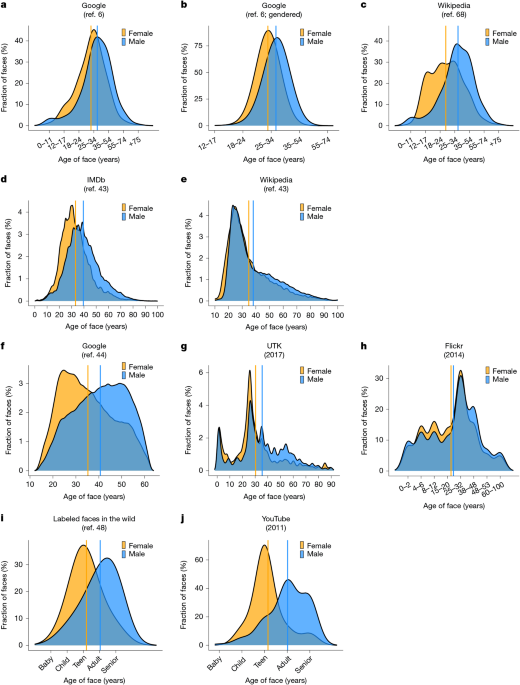

The numbers don't lie. While battery electric vehicles (BEVs) now command 90% of the zero-emission vehicle market, hydrogen cars struggle to maintain 0.1% despite massive government subsidies.

The Physics Problem: Energy Inefficiency At Every Stage

The fundamental flaw with hydrogen vehicles begins with basic thermodynamics. Unlike electricity that can flow directly from power plants to batteries, hydrogen requires multiple energy-intensive conversion steps that bleed away efficiency at every turn. Consider the complete energy pathway:

First comes production. Today, 95% of hydrogen is made through steam methane reforming, a fossil fuel-dependent process that emits 9-12kg of CO2 for every 1kg of hydrogen produced. The cleaner alternative, electrolysis using renewable energy, wastes 30% of the input electricity during the water-splitting process alone.

Then comes compression and transportation. Hydrogen must be compressed to 700 bar (10,000 psi) for vehicle use, consuming another 12-15% of its energy content.

Transporting this ultra-light gas requires either energy-intensive liquefaction at -253°C (losing another 30-40%) or expensive composite tanker trucks that can only carry enough hydrogen to power 60 vehicles compared to 6,000 gallons worth of gasoline in a standard tanker.

Finally, the fuel cell itself converts hydrogen back to electricity at just 50-60% efficiency. When you tally up the entire well-to-wheel cycle, a hydrogen car consumes 3-4 times more renewable electricity per mile than a battery electric vehicle.

In an energy-constrained world prioritizing decarbonization, this inefficiency borders on criminal negligence.

The Infrastructure Trap: A Chicken-and-Engine Problem

Hydrogen's infrastructure challenges make early EV charging networks look trivial by comparison.

While electric vehicles can charge anywhere with basic electrical service (and are now supported by over 150,000 public charging points in the U.S. alone), hydrogen requires an entirely new parallel infrastructure with astronomical costs.

Building a single hydrogen fueling station runs $2-4 million, 100 times more expensive than installing a fast charging hub. The reason is that hydrogen's low energy density requires specialized cryogenic pumps, explosion-proof construction, and constant deliveries by those inefficient tanker trucks.

Even California's heavily subsidized "Hydrogen Highway" has only managed to deploy about 60 stations after 20 years of effort, while Tesla built over 1,500 Supercharger stations in half that time.

This creates a fatal adoption cycle: consumers won't buy hydrogen cars without stations, and energy companies won't build stations without vehicles.

Meanwhile, BEVs leverage existing electrical grids that already reach every home and business. The infrastructure math is so lopsided that even ardent hydrogen advocates admit widespread deployment would require trillions in investment, money that could decarbonize dozens of other sectors more effectively.

The Economic Reality: Why Hydrogen Cars Can't Compete

On a pure cost-per-mile basis, hydrogen loses spectacularly to both gasoline and electricity. Even with generous subsidies, hydrogen fuel costs $13-16 per kilogram in California, translating to about $0.30 per mile.

Compare this to $0.05 per mile for a BEV charging overnight, or $0.12 for a gasoline hybrid. The vehicles themselves carry equally punishing premiums, with the Toyota Mirai leasing for $50,000 while offering inferior performance to a $30,000 Tesla Model 3.

Maintenance presents another economic hurdle. Fuel cells require expensive platinum catalysts and degrade faster than batteries in real-world use. The average hydrogen car loses about 5% of its range annually as the fuel cell membrane deteriorates, a problem lithium-ion batteries solved years ago.

When Hyundai surveyed its Nexo fleet, fuel cells were lasting just 60,000 miles before needing replacement at $30,000 per unit. That's a fatal flaw for any mass-market technology.

Why The Hydrogen Fantasy Persists

Given these overwhelming disadvantages, why does hydrogen maintain such vocal support? The answer lies in a potent mix of corporate interests and technological romanticism.

Oil companies love hydrogen because it preserves their refinery and distribution infrastructure. The same pipelines that move natural gas can theoretically transport hydrogen (with expensive modifications).

Automakers invested in fuel cells see them as a way to maintain proprietary powertrain expertise as EVs commoditize. And politicians appreciate hydrogen's promise of "clean" energy without challenging existing energy giants.

Silicon Valley's fascination stems from different psychology: The allure of complex engineering solutions over simple ones. Battery EVs represent incremental improvement (better chemistry, faster charging), while hydrogen offers the sexier narrative of total energy transformation.

This explains why figures like Elon Musk (a pragmatist) dismiss hydrogen cars as "mind-bogglingly stupid," while more ideologically driven tech leaders continue championing them against all evidence.

The Niche Where Hydrogen Might Survive

This isn't to say hydrogen has no role in decarbonization. For heavy trucking, maritime shipping, and possibly aviation - applications where battery weight becomes prohibitive - hydrogen may find limited use. But even here, the economics remain questionable compared to advancing battery technologies and renewable synthetic fuels.

The passenger vehicle market, however, has clearly spoken. Global automakers have quietly shelved hydrogen programs as battery costs plummet below $100/kWh.

Toyota - hydrogen's last true believer - now sells 10,000 BEVs for every Mirai it moves off lots. Meanwhile, charging times for EVs now rival gas stops with 800V architectures delivering 200 miles in under 10 minutes - eliminating hydrogen's last perceived advantage.

The End Of My Hydrogen Rant

Hydrogen cars represent the triumph of hope over physics. Like flying cars or personal jetpacks, they capture our imagination while ignoring practical realities. The numbers are clear: for every dollar invested in hydrogen mobility, we could achieve three times the emissions reduction putting that money into battery EVs, grid upgrades, or renewable generation.

The hydrogen car experiment has given us valuable lessons about energy systems and the importance of efficiency. But after 30 years of unfulfilled promises, it's time to call this failed technology what it is - a $20 billion detour on the road to sustainable transportation that we can't afford to keep exploring. The future is electric, and every day we spend pretending otherwise is another day wasted in the climate crisis.

.png)