We’ve been lying to ourselves about our tests for years. We’ve been telling ourselves we’re “testing what users do” while secretly giving our tests superpowers no user has ever possessed. Perfect memory of every CSS class. Instant knowledge of every button’s location. The ability to click things that are technically visible but practically invisible.

My tests have been pretending to be users the way a GPS pretends to be a navigator. Basically accomplishing the same goal, but missing something fundamental about the lived experience of trying to navigate downtown Pittsburgh’s highways at full speed.

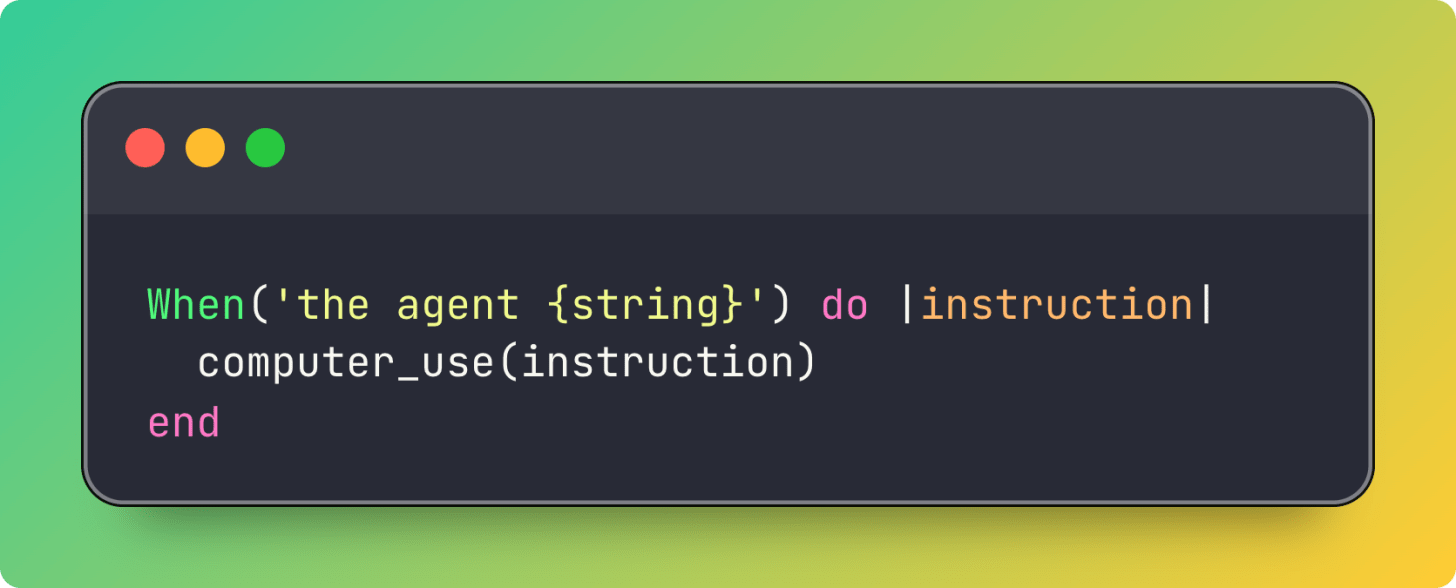

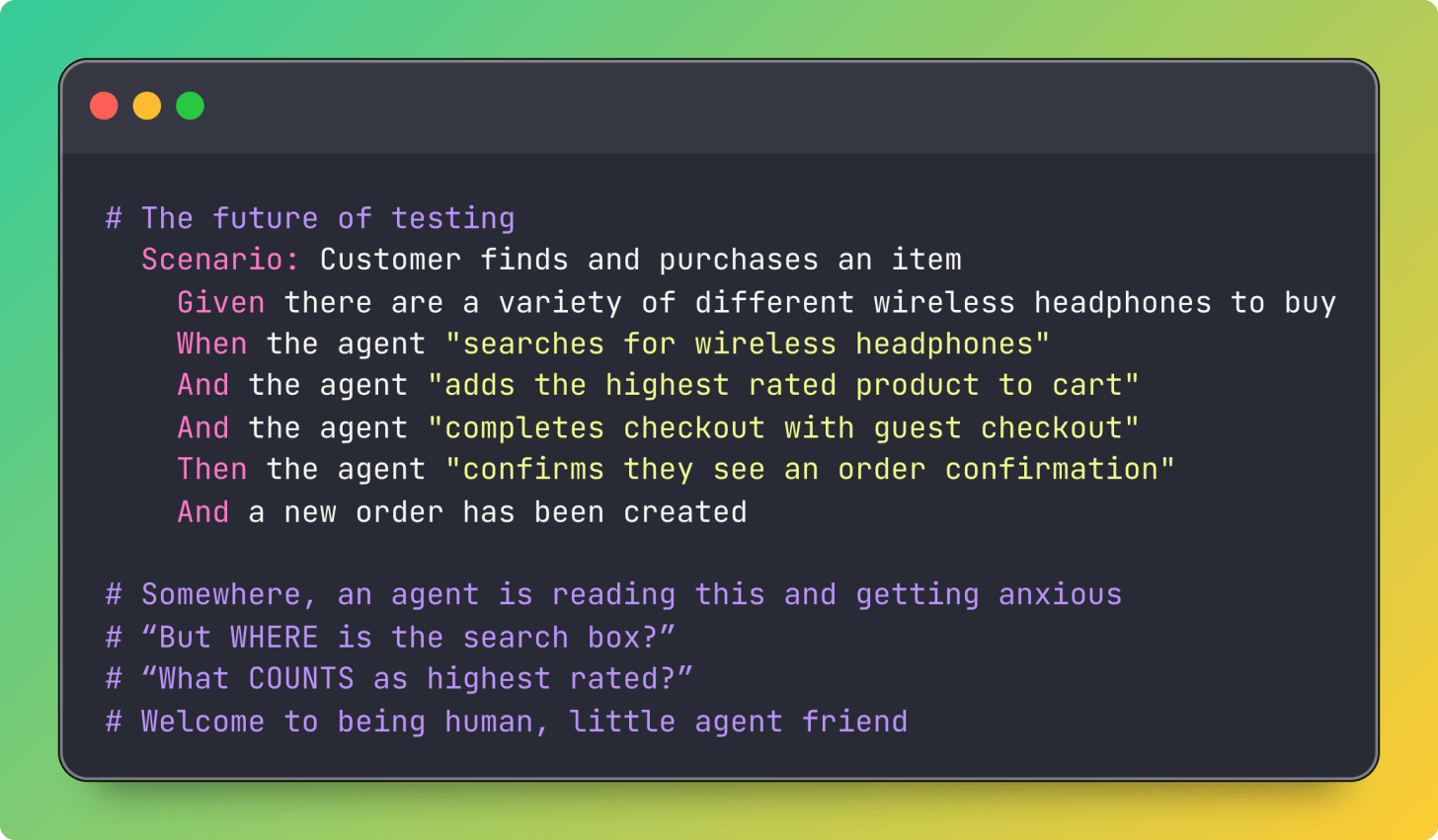

And then one night, I wrote this Cucumber step after seeing Gemini’s Computer Use model get released and I’ve been thinking about the implications ever since.

It’s so simple. What it does is send an instruction to the computer use agent. The agent looks at a screenshot of your website and attempts to do what you asked. It might succeed or it might fail spectacularly.

And when it fails? Well... that’s kind of what I want to talk to you all about today.

I’ve been writing integration tests for years. You probably have too. And somewhere along the way, we all made the same quiet compromise: we taught our tests to be better at using our websites than our users are.

We gave them perfect knowledge even though we know we shouldn’t. DOM selectors. CSS classes. The exact pixel coordinates of every button. We turned them into tiny mechanical gods who never misunderstand instructions, never misread labels, never click the wrong thing because two buttons look similar. Who wants to deal with a flaky test when you know the feature works?

Traditional tests are liars. They pretend to be users, but they’re not. They’re automation scripts with perfect knowledge of your DOM structure. They never misread instructions. They never think the search box is a login field. They never click “Subscribe to Newsletter” when they meant to click “Continue.”

An agent? An agent can be confused. It can misinterpret your UI. And when it does, maybe (just maybe) that’s because your UI is confusing.

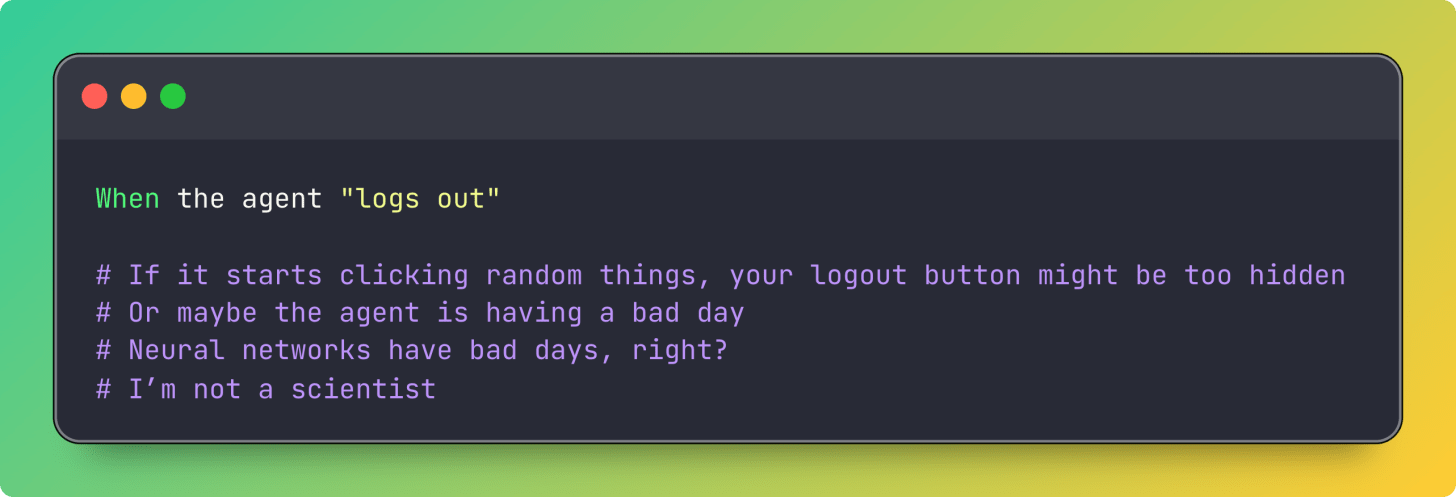

When you hardcode click_button(‘Logout’) in your test, you’re testing that a button with that exact label exists. But what are you really trying to test? You’re trying to test that someone can log out. That the flow makes sense. That it’s discoverable.

When you write:

You’re testing the concept of logging out. Not the implementation. The agent has to figure out where the logout button is, what it’s called, whether it’s in a dropdown menu, whether it requires confirmation. Just like a user would.

This is testing something softer than “does this DOM element exist?” Something harder to measure. Something like: “Can a reasonable entity figure out how to do this thing on your site?”

And “reasonable entity” here includes:

Your users

Your users’ AI assistants

Future AI agents trying to buy things/book appointments/cancel subscriptions

You, after three glasses of wine, trying to remember how to change your password

The more I think about this patten, the more it feels like I stumbled on something accidentally bigger than intended. It was really just supposed to be a fun experiment to share on this newsletter.

Traditional BDD goes:

Write a test describing user behavior

Watch it fail

Implement the feature

Watch it pass

Agentic BDD (A(b)DD? ABDD? Someone help me name this and we could go halfsies on the lucrative book deal) could go:

Write a test describing user behavior

Let an agent try it

Watch it fail in fascinating ways

Send those failures to your coding agent

Have the agent implement what’s needed

Run the test again

Repeat until you run out of token quota or your sprint ends, whichever comes first

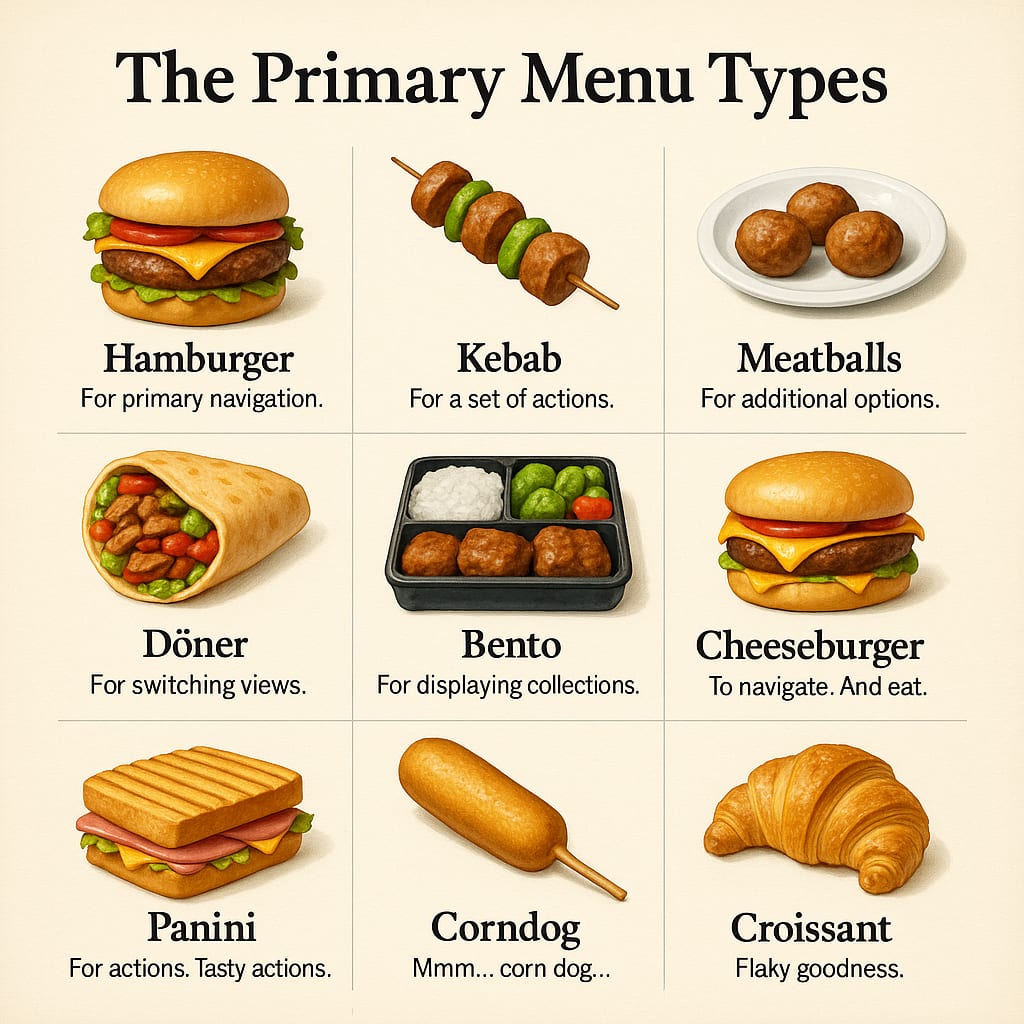

Instead of turtles all the way down, it’s agents, and they’re all doing their best to understand your menu iconography.

I can already see your objections forming (I’ve already heard some of them)

Won’t this be flaky? (Probably)

Won’t this be really slow? (Definitely)

Will this make your CI bill look like a phone number? (Maybe)

Will this actually catch bugs that matter? (I think so?)

Am I just making elaborate excuses to play with AI? (...)

The agents sometimes hallucinate success. They’ll confidently report that they completed a task when they absolutely did not. They’re like that friend who says “yeah, I know exactly where we’re going” while their GPS keeps yelling at them to make a U-turn.

Your selenium tests will never tell you that your logout button is too small. Your selenium tests don’t care. They have the CSS selector. They’re machines with perfect knowledge pretending to be users.

Your agent tests? They might just accidentally tell you the truth.

So you’re probably thinking, “Okay, this sounds simultaneously ridiculous and intriguing, how do I actually try this?”

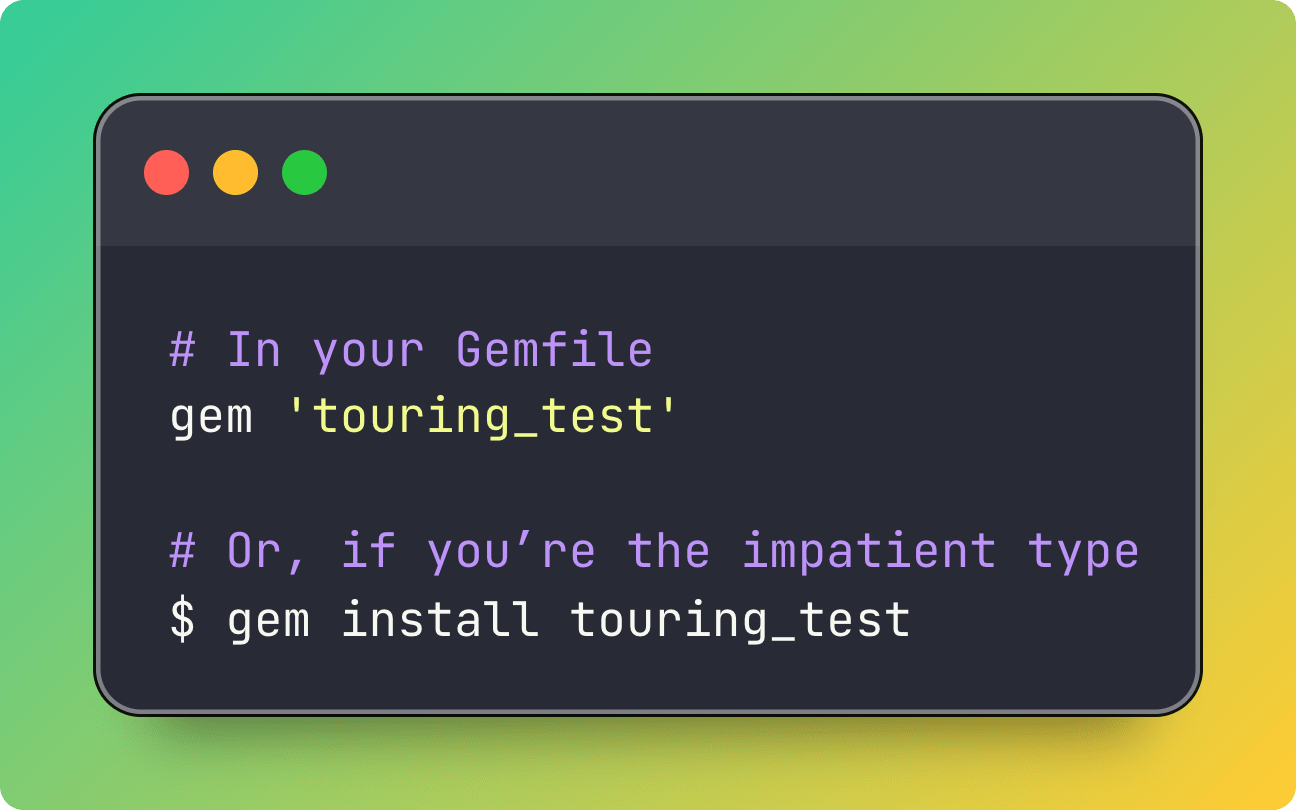

The gem is called Touring Test.

Yes, like the Turing test, but for touring your application. Like a confused tourist with a camera and an inability to read maps. Get it?

That’s it.

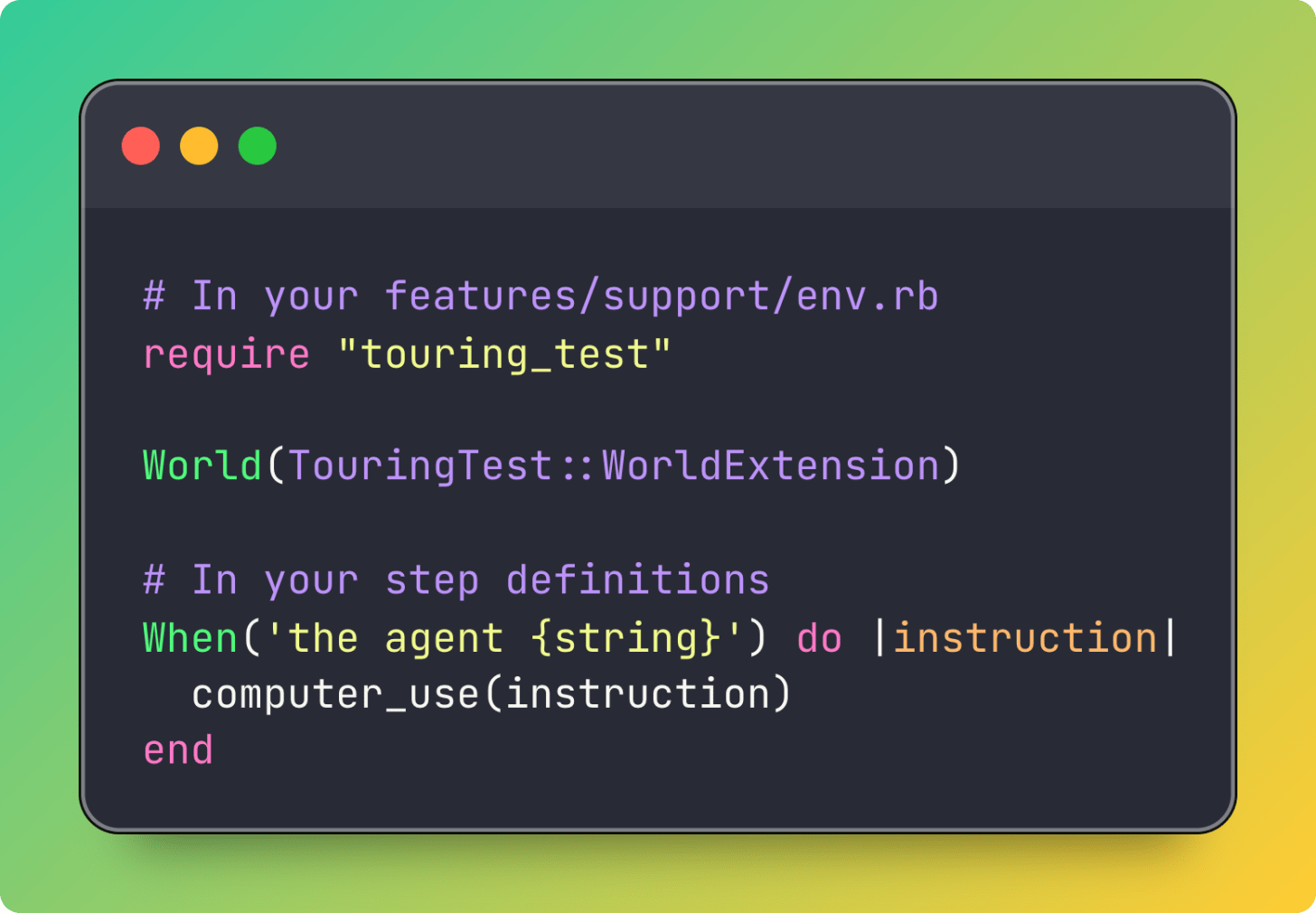

Then you set up your API key (currently only supports Gemini, but there’s no reason it can’t be expanded to use any of the computer use tools and models). The gem README has instructions, but honestly, if you’ve made it this far into this article, you probably know how environment variables work.

And now you have a test that can get confused. Congratulations? I think?

The code is up on GitHub (under a new org I just set up for this newsletter, Works On Your Machine, where I’ll be putting stuff going forward). You can look at it. You can judge my choices. You can submit issues and leave me thank you notes about how easy to use your UI has become.

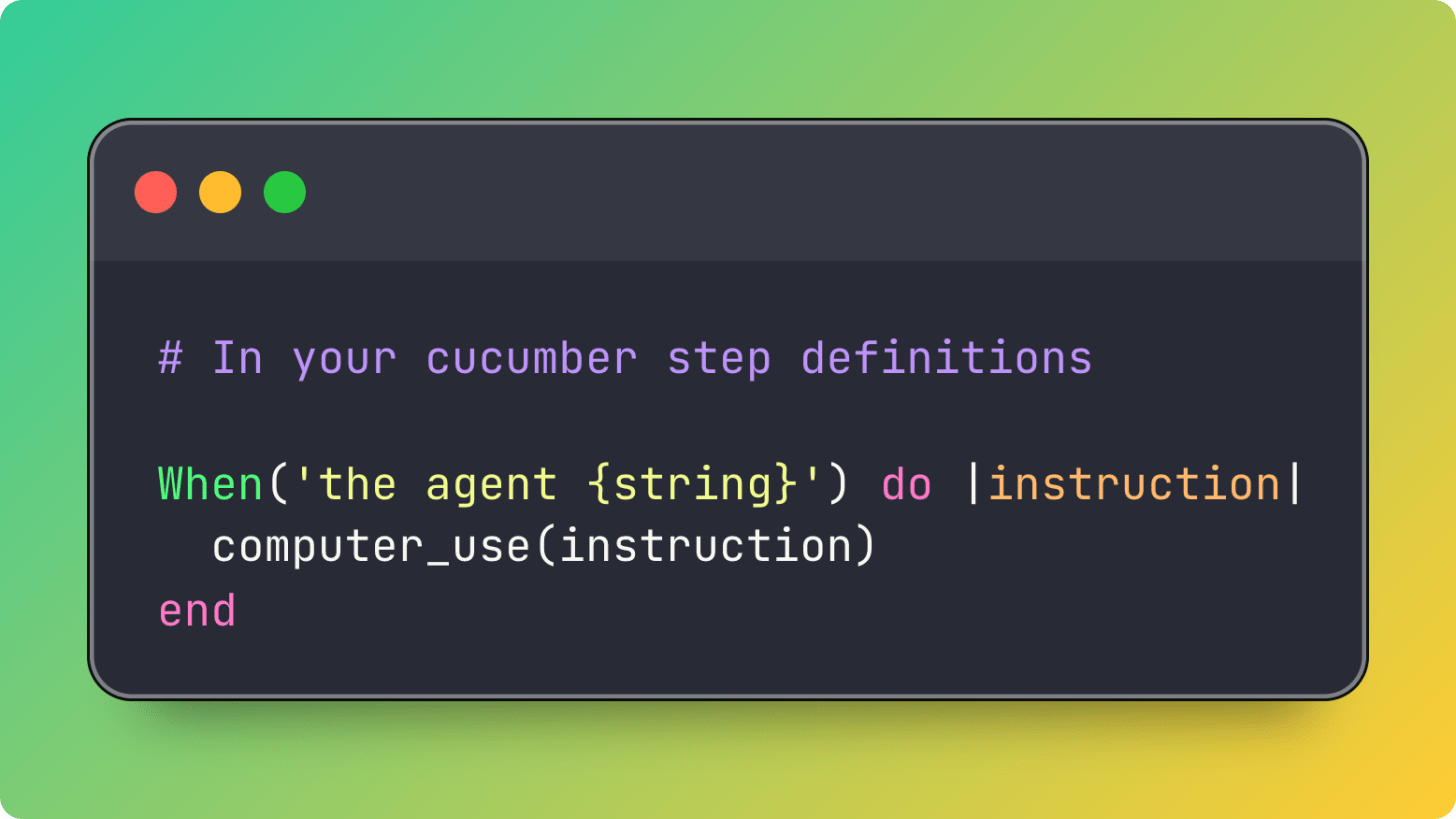

The way I’m using it is exactly what you saw above in this post:

That’s it. That’s the step. Under the hood, computer_use does something like:

Takes a screenshot of the current browser state

Sends the instruction + screenshot to Gemini’s computer use model

The agent decides what to do (click this, type that, scroll here)

Executes those actions (as tool calls)

Takes another screenshot

Repeats until it thinks it’s done or gets confused enough to give up

The agent has access to:

What the page looks like (literally, as an image)

What the instruction was

The ability to click, type, scroll, and navigate

No knowledge of your DOM structure

No knowledge of your button labels

No knowledge of your app’s architecture

Just like a user. A very determined, slightly confused user.

We spent decades making tests that were good at pretending to be users. We gave them superhuman powers and called it “automation.”

But maybe we automated the wrong thing. Maybe we automated the execution when we should have been automating the confusion.

Real users get confused. Real users misclick. Real users can’t find the logout button even though it’s right there, right there, in the navigation menu that you spent three weeks perfecting.

An agent that can get confused? That can misunderstand your UI? That can fail in frustratingly human ways?

That’s not a bug.

.png)