In a severe drought year, like this one, some farmers and ranchers in the Yakima River Basin come to expect a letter from the state cutting off one of their main water sources, and they plan accordingly.

But this year’s drought was so bad, the state had to cut deeper than ever before.

With only a single exception, every person, farm, ranch, irrigation ditch and company drawing water from rivers, streams and reservoirs within the basin had to stop. Entire cities couldn’t be spared.

This includes Cle Elum, Ellensburg, Prosser, Roslyn, Yakima and anyone else with a surface water right. They all received so-called curtailment letters from Washington’s Department of Ecology earlier this month. Only the Yakama Indian Nation’s water was left untouched.

This means no more irrigation, lawn or garden watering through the end of the month. People aren’t going without water inside their homes because most cities do have other sources of water from which to pull or special considerations from the state. But residential cuts are a concern for the years ahead if such conditions return or worsen.

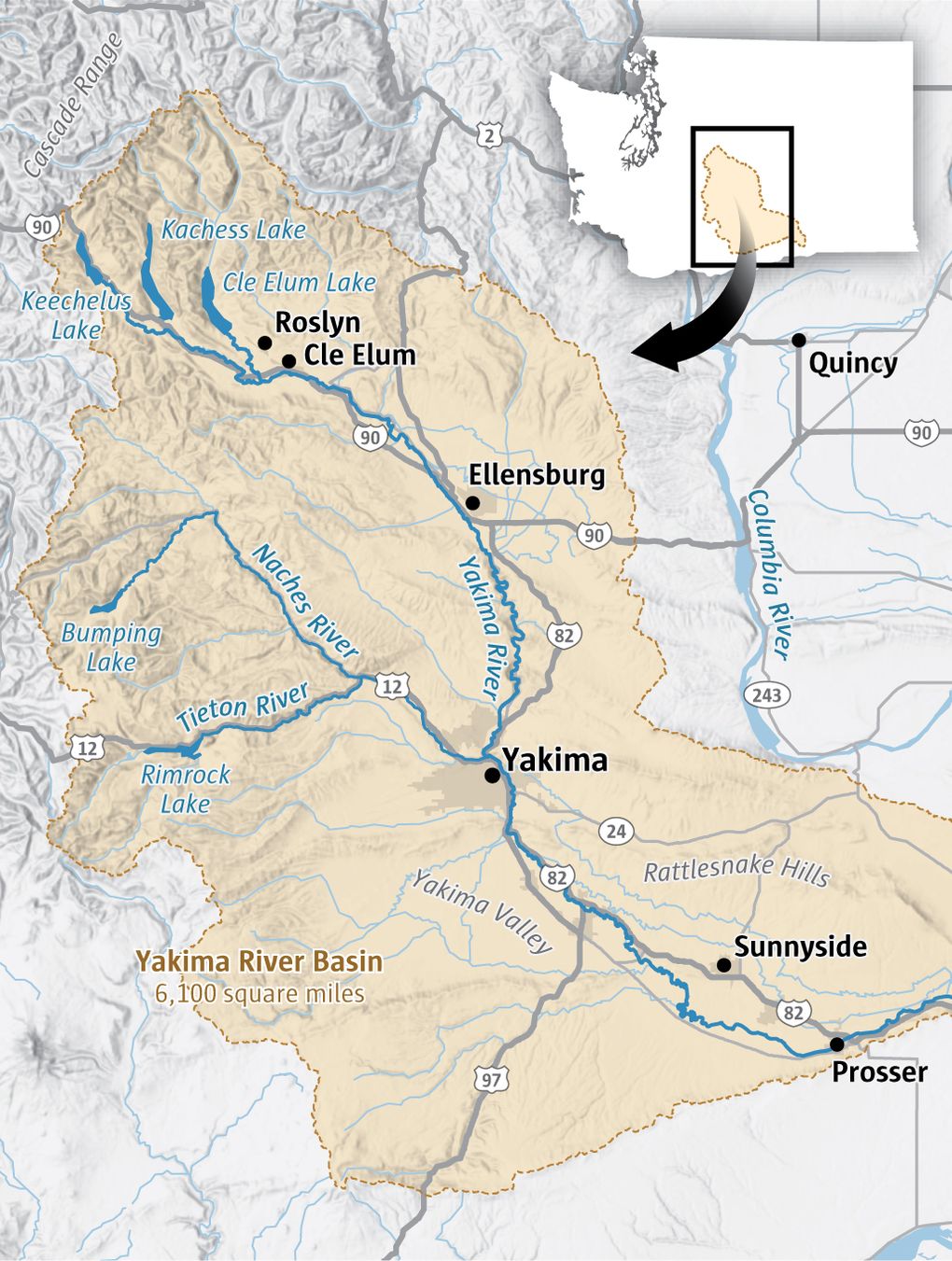

Cities forced to cut water use along the Yakima River

As Washington’s third severe drought year in a row deepened, state officials sent letters to every city and township holding a surface water right within the Yakima River basin, requiring them to stop drawing water from rivers and streams. Those cities include Cle Elum, Ellensburg, Prosser, Roslyn and Yakima. This marks a significant and unprecedented development in the series of droughts plaguing the region.

Some cities have alternative water sources on which they can fully rely or supplement a portion of their peak demand. But not every city has a backup water source.

“I’ll be honest with you, we don’t have one,” said Roslyn Mayor Jeff Adams.

The small town has largely kept water on for residents’ homes by restricting outdoor use and because state regulators say they were more concerned about larger-scale water users than the few homes there.

Never before has drought forced the state to cut off water sources for entire cities, marking a new low for the warming and drying region and a warning for the future.

First in time, first in right

Put simply, surface water use in Washington runs on a seniority system. A farm, say, might have a legal right to draw so much water from a specific river or creek. The year that right was adjudicated in court serves as a time stamp.

The older a water right is, generally, the more valuable it is.

In times of drought, when a river is running low, there’s not enough water to go around. So Ecology will tell certain rights holders that they can’t have their full share. The first ones cut are the youngest, also called junior rights holders. Here, rights younger than 1905 are considered junior and they come to plan around these expected cuts as best they can. Senior water rights holders are generally much safer from the cuts.

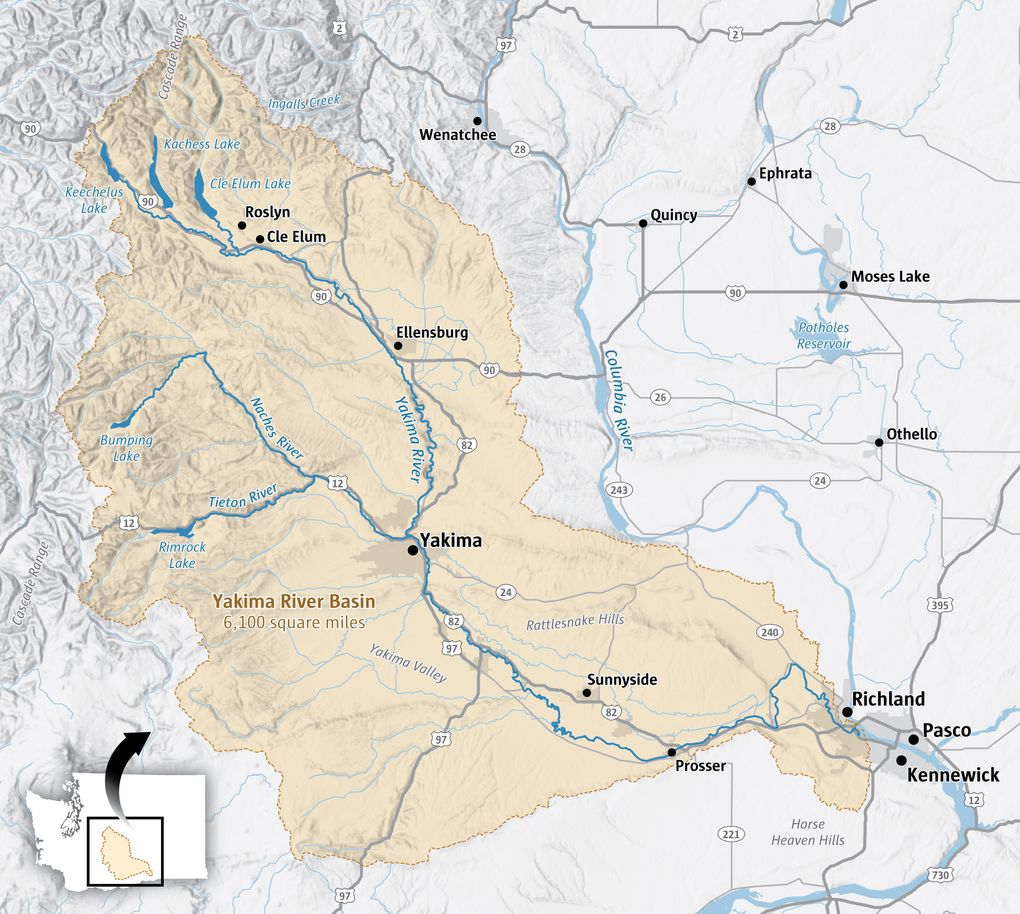

Not this year, though. Drought conditions east of the Cascade crest are so dire that state officials cut off everybody’s surface water rights within the 6,100-square-mile basin, no matter their seniority, which hasn’t been done before. Only the single most senior right, held by the Yakama Indian Nation and dated 1855, remained intact.

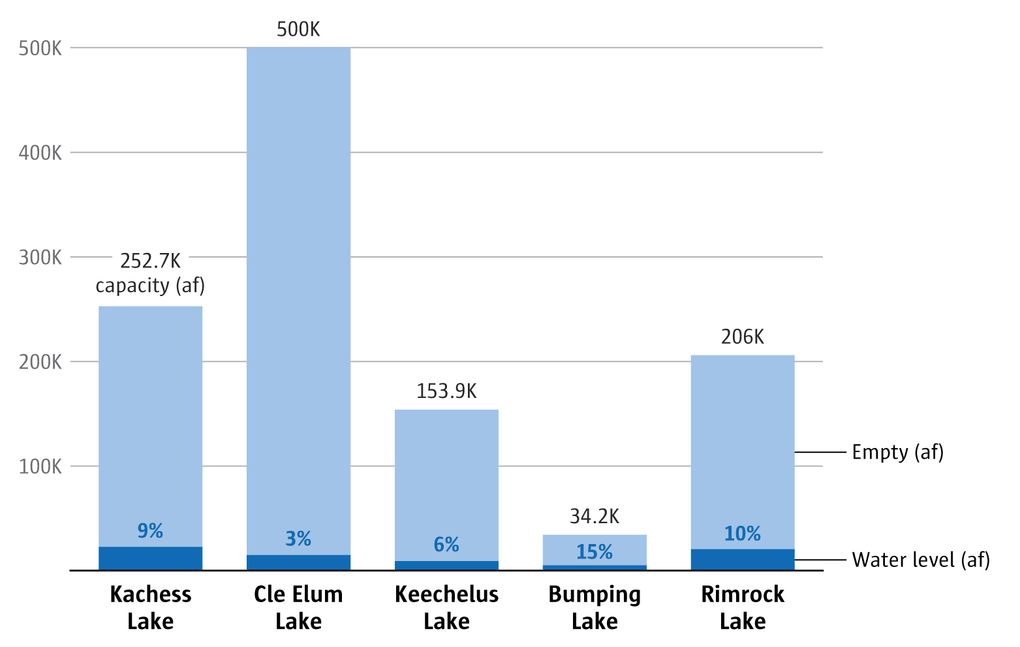

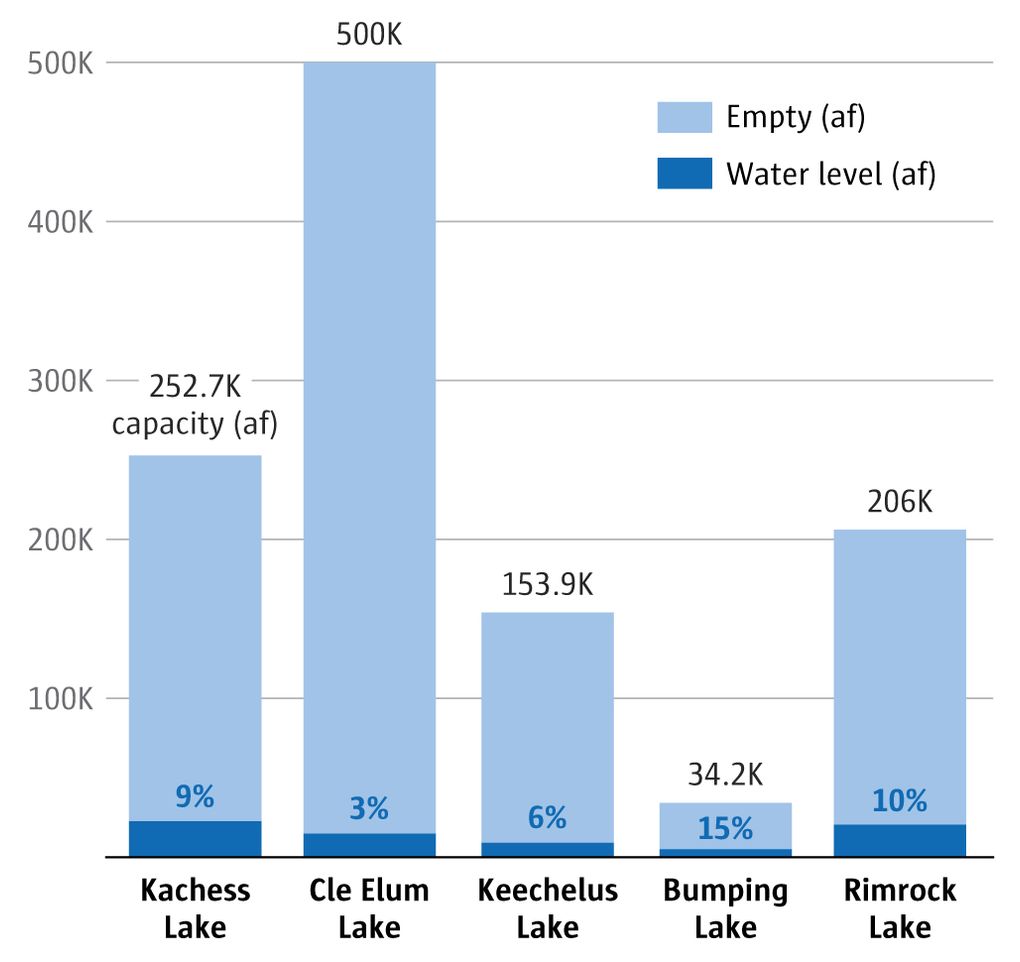

The five reservoirs throughout the basin, Bumping Lake, Cle Elum, Kachess, Keechelus and Rimrock effectively ran out of water at the start of the month. This is normally their lowest point of the year, said Caroline Mellor, a drought coordinator with Ecology. Even so, they’re still sitting at a fraction of their normal levels.

Yakima reservoirs far below capacity

Yakima River Basin’s reservoirs are currently at 7% of their total capacity, or 72,477 acre feet of the 1.06 million acre feet capacity.

Because this is Washington’s third drought year in a row, the region started off on the wrong foot, with parched soils and thirsty vegetation. The mountains saw so little snowpack (and an early melt-off) this winter that state officials declared a drought emergency before the season ended, expanding its scope later in June. And over the summer months, Yakima and Kittitas counties saw 29% and 35% of their normal precipitation, respectively, Mellor said.

Much of the basin is a desert, said Heather Simmons, a water resource program section manager with Ecology, and with too little water in the waterways, local, state, federal and tribal officials must find new ways to conserve the resource.

In the short term, that inevitably means cuts for farms, ranches and even cities. In all, about 1,365 water rights holders lost surface water access until the end of October, Simmons said.

Surface water is drawn from rivers, streams and reservoirs. Groundwater is drawn from different types of wells. Cities, farms, ranches and more can use one of those options or a mix of both to pipe into kitchen sinks, irrigation canals or even livestock yards. That specific mix will depend on things like their location, available water rights and money for infrastructure.

Cutting off a surface water source could mean eliminating a city’s water supply or it could only limit its ability to irrigate lawns and gardens. The severity of these cuts depends on how diverse a city’s water supply might be.

The city of Roslyn, for example, only has access to surface water.

Cities of the basin

City officials in Roslyn understood for decades that water shortages loomed over their small community northwest of Cle Elum, said Mayor Adams. For generations, the city of perhaps 1,000 people has relied on a single source, called the Domerie Creek water right.

Every so often the state would require them to cut perhaps 25% or 30% from their junior water right dating back to 1908, Adams said. But if the city was ever required to cut off surface water completely, like it was this year, it had no alternative water source. Theoretically, in that case water could be shut off completely, not just to lawns and gardens but to people living in the area.

So around 2009 city officials bought two senior water rights, one dated 1885 and another dated 1875, Adams said. These would safeguard Roslyn’s water supply in case of a full-blown curtailment.

They were wrong.

Ecology cut junior and senior water rights alike throughout the basin this fall, rendering Roslyn’s senior rights effectively useless.

While the curtailment technically meant the city’s entire water source should have been shut down, Simmons said Ecology was less concerned about policing indoor water use in small places like Roslyn than making sure major users (which can draw millions of gallons a day) were conserving the resource.

Adams said the city itself stopped irrigating on municipal properties, imposed an outdoor watering ban and asked residents to conserve in their own homes. Other cities imposed similar restrictions.

But in the future, Roslyn is going to need a backup water source, Adams said. Likely, the city will be forced to drill groundwater wells, on which it could rely if such statewide restrictions return.

Those won’t come cheaply, though. The senior water rights cost Roslyn about $600,000 in 2009 (with the help of a $400,000 grant from the state), Adams said. That’s a tall order for a city with a general fund averaging perhaps $2.5 million.

Even so, finding new water sources will have to be a top priority for the city moving forward, Adams said. Because while this year’s curtailment didn’t necessarily mean people lost water within their own homes, it’s certainly a warning for droughts in the future.

“This isn’t to be ignored,” Adams said. “This is to be taken seriously.”

Yakima, on the other hand, does have a backup, said Mike Shane, the city’s water and irrigation division manager. But it’s not enough.

The city has about 72,000 residential water customers and another 11,000 irrigation customers, Shane said. And its main water source draws from the Naches River but it also has a series of groundwater wells.

Say the surface water freezes in the winter or perhaps there’s a quality concern, Shane said the city can turn off its surface water and switch over to the wells. That’s what it did in this case to ensure residents still had water in their homes.

However, the groundwater wells can only produce about 13 million gallons of water a day while the surface water source can provide about 20 million gallons, Shane said. The city’s peak water demand sits somewhere between those two numbers.

So if similar restrictions struck the city again during the wrong time, there could be a shortfall, Shane said.

To solve the problem, city officials want to drill new aquifer storage and recovery wells, Shane said. This would allow them to pump excess water underground during the wet months and store it there until it’s needed. The city has permission from Ecology for the work, but it doesn’t yet have the money or planning needed.

This year’s drought underscores the need to shore up Yakima’s water supply system, Shane said.

Other cities, like Ellensburg, rely almost entirely on groundwater for their water supply and so they didn’t feel as much of a pinch from this year’s curtailments.

Groundwater isn’t an unlimited resource, however. Really, it’s dwindling across the American West, the same as many rivers and streams.

In the long run, virtually every aspect of water use across the Yakima River basin must be reconsidered as the resource continues to dissipate. Additional storage, conservation and even crop rotations will play a part in the years ahead but people throughout the region acknowledge there isn’t any single solution.

Snow droughts can be expected four years out of every decade and additional warming trends will melt snowpack and evaporate remaining water much quicker than before.

Already this season eyes turn toward the Cascades, hoping for snow and rain.

Conrad Swanson: 206-464-3805 or [email protected]. Conrad Swanson is a climate reporter at The Seattle Times whose work focuses on climate change and its intersections with environmental and political issues.

.png)