She sat at an empty desk, staring into space. And then, spent an entire day riding the elevators up and down, repeatedly. She happily chatted with others as they exited and entered, explaining that “she’s just going for a ride.” When pressed as to why she was doing this, she said, “It helps her think from a different perspective”. At her desk, she was doing 'thought work’ and working on her ‘thesis’.

In 2008, employees of the accounting firm Deloitte in London were deeply troubled by the behaviour of this young woman. Urgent emails were getting exchanged, wondering how to make sense of this. For months, Johanna, the marketing trainee, would show up at her job and literally do nothing. She filmed herself at her desk, inert. Shots of her sitting still are interspersed with emails to HR from her colleagues suggesting she is deranged (which she was able to procure after being fired), as well as conversations with questioning coworkers, whom she told she was “doing brainwork.”

It turned out that, unwittingly, the employees had taken part in a performance piece called The Trainee. Johanna was actually Pilvi Takala, a Finnish artist who is known for threatening social norms with simple actions.

There is inherently nothing unusual about doing nothing at work. In periods of lull and boredom, we indulge in chat in breakrooms, look at our phones or maybe even read this piece on Substack. It was the threat of doing nothing, upending the general order and flow of the workplace, that deeply unsettled people. On her website, Takala goes on to say

What provokes people about this ‘non-doing’, aside from the strangeness, is the element of resistance.

If I were in that Deloitte office in 2008, I would have been one of those people, completely bewildered at her behaviour.

So embedded are social norms in our lives that we often follow them, unfailingly. And what we are often unable to do is to put up resistance to them.

Consider this

You delete Instagram every week, only to download it back again, as you struggle to sleep at 2 am. After yet another endless round of doom scrolling, you curse yourself, becoming acutely conscious of your brain rot. You are overtaken by an urge to redesign your life. You vow to work out regularly from tomorrow, get back to reading for at least 30 minutes every day and stop buying the coffee mugs and home decor stuff that Instagram keeps showing you. You promise to finish that online course you signed up for and decide that you’ll meet your friends more often, IRL, and not just DM reels to each other. From the dark recesses of your mind, you bring out the buried idea of the novel you have been intending to write ever since you left university. The novel has changed six times by now, because you have changed, and yet no version of it has been written. You tell yourself, “This year, I am going to do it”. You feel energised, driven by purpose and feel you’ve turned a corner. With your head buzzing with the images of a spectacular arrival of your ideal self, you somehow manage to sleep.

Before the first rays of the sun could warm up your face, your eyes reflect the brightness of your smartphone screen. Within minutes of waking up, you are glued to your phone, and you are not the exception. 84% of people check their phones within 15 minutes of waking up. You vaguely remember the lofty plans from last night, but they are currently being drowned in the caffeine, as your sleep-deprived self is rushing to work, preparing for the existential dread that defines modern work. There wasn’t any time left for the morning workout, but at least you messaged that friend of yours to make plans to meet over coffee. You get onto the bus, and hop onto Reels/TikTok, looking to Booktok reels, satiating the ‘reader’ in you, and make a mental note of the next book to pick up, to add to the ever-growing pile of books you will never read.

At work, you see people in the breakroom talk about that nth productivity hack that will launch them into a state of work nirvana. You listen to your manager talk about next year’s targets, and how you will get there, one logical step after another. You have a sense of déjà vu, for this plan sounds exactly like the one in your last job. In fact, it sounds pretty much like what everyone in the industry does. Albert Einstein allegedly said that ‘Insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results’. But then he was thinking of trivial things like quantum mechanics and the nature of spacetime, and he had not encountered the geniuses that run your office. The plan to double the marketing campaigns’ CTR (click-through rate) is set in motion, and while it makes no sense to you, you play along. You have long recognised that you have a Bullshit Job. You return home, too tired to read, write or have a meaningful conversation with anyone. You sink into the couch, dinner in tow, and absent-mindedly put on Netflix, without actually paying attention. So much so that Netflix actually changed the way some shows are being written to account for you not being mentally present. As Derek Thompson notes in this brilliant piece Everything is Television (also quoting Will Tavlin from here)

Netflix producers reportedly instruct screenwriters to make plots as obvious as possible, to avoid confusing viewers who are half-watching—or quarter-watching, if that’s a thing now—while they scroll through their phones.

Several screenwriters who’ve worked for the streamer told me a common note from company executives is “have this character announce what they’re doing so that viewers who have this program on in the background can follow along.” (“We spent a day together,” Lohan tells her lover, James, in Irish Wish. “I admit it was a beautiful day filled with dramatic vistas and romantic rain, but that doesn’t give you the right to question my life choices. Tomorrow I’m marrying Paul Kennedy.” “Fine,” he responds. “That will be the last you see of me because after this job is over I’m off to Bolivia to photograph an endangered tree lizard.”)

More from Will Tavlin

In 2021, Netflix briefly introduced a new feature on its home page, called “Play Something,” to help in what the streamer called “times when we just don’t want to make decisions.”

“Play Something,” as in: play anything. It doesn’t matter if it’s good or bad, if a user is on their phone or cleaning their room. What matters is that it’s on, and that it stays on until Netflix asks its perennial question, a prompt that appears when the platform thinks a user has fallen asleep: “Are you still watching?”

Unfortunately, we still are. We are drowning in content, news and social media. This is no more a matter of personal circumstance or quirk; it is a social norm and a civilizational malaise.

This is not a critique of Netflix, but of the entire tech ecosystem as a whole, the worst of all being social media. Gurwinder, in his piece, How Social Media Shortens Your Life, makes a remarkable observation about how we keep time

Traditionally, stories were linear and syntagmatic, each moment of the tale semantically follows from the previous - collective meaningfulness anchors the whole thing in memory. We are better at memorizing information when its in narrative form. Hence they are good timekeepers, and we keep sense of time through emplotment: By turning time into stories.

Social media feed is a chronological maze, no beginning, no end, or middle. Our attention is engineered in ways that we waste more time, regret it less and create more FOMO to return through push notifications.

As our sense of time becomes warped, we start to lose our attention. We constantly switch between real and virtual worlds, and this makes us lose track of time.

At the heart of it is Silicon Valley’s obsession with money. Money follows attention, and the more attention that can be captured, the more money can be made for Wall Street investors.

A close second is its obsession with logic and rationality. Every decision, even the one above that feels banally evil, is justified by rationality. Engagement dashboards in corporate offices identify ‘watch time’, ‘content abandonment’ as metrics to be tracked, maximised or minimised, completely delineated from the fact that there are flesh and blood human beings behind aggregated numbers.

Silicon Valley’s obsession with rationality is rooted in a belief that logic and technology can solve complex problems, leading to a technocratic and utopian view of the future that some link to ideologies like Effective Altruism, some of which evolved into rationalist cults, which when taken to their extreme, are exemplified by a loose group of vegan anarchist transhumanists nicknamed the Zizians, have been linked to six violent deaths. There is an unhealthy obsession with Stoicism - and while it does centre on reason and logic, it also focuses on how one must be free from the passions of distress, fear, lust and delight, most of which are found in abundance in this ecosystem. And the irony is that an actual stoic has feelings of good intent and moral shame (among others), feelings that are not in the same local group as Silicon Valley.

The problem is not with logic per se, because it is one of the most powerful tools available to mankind. The problem is with its deification, it being held as the utmost truth, akin to a religion. But the roots of this problem far predate the world of startups and venture capital, because they are firmly embedded in the crowning glory of Western intellectual thought, the Enlightenment Project.

How the Enlightenment deified logic and gave intuition a bad rep

The female is softer in disposition, is more mischievous, less simple, more impulsive, and more attentive to the nurture of the young; the male, on the other hand is more spirited, more savage, more simple and less cunning … The fact is, the nature of man is the most rounded off and complete, and consequently in man the qualities above referred to are found most clearly. Hence woman is more compassionate than man, more easily moved to tears, at the same time is more jealous, more querulous, more apt to scold and strike. She is furthermore, more prone to despondency and less hopeful than the man, more void of shame, more false of speech, more deception, and of more retentive memory.

Polarising males and females in terms of both intelligence and character, these are the words of Aristotle. His view of women being inferior to men was emblematic of the times. This passage echoed through millennia of European debate about the difference between the genders and structured early modern views about moral values in Christianity.

Memory, imagination and sociability were the traits associated with women. In contrast, men were associated with discursive and speculative reason. As per the German philosopher, Immanuel Kant, this contrast condensed into the male mastery of abstract principles, as opposed to the female grasp of concrete detail. He said “Her philosophy is not to reason, but to sense”.

A century later, Darwin similarly opposed male energy and genius to female compassion and powers of intuition. Modern psychology absorbed this opposition between male logic and female feeling into its initial concepts.

Over the centuries, the associations between intuition and women have been one between what were viewed as a lesser virtue and a lesser sex.

However, there is little firm evidence that men and women differ in any striking way in their cognitive capabilities.

But what is intuition, and what are gut feelings? Let us dive into that

What is Intuition?

One of the simplest ways to understand it is - What happens when a woman feels that a creepy guy is around her? Almost every woman reading this knows what I'm talking about (If you are a man, please go ask a woman about it!)

Without explicitly knowing that the guy is creepy, she knows (often correctly) that he is, because we say her gut feeling says so.

Gut feelings are what we experience. They appear quickly in consciousness; we do not fully understand why we have them, but we are prepared to act on them.

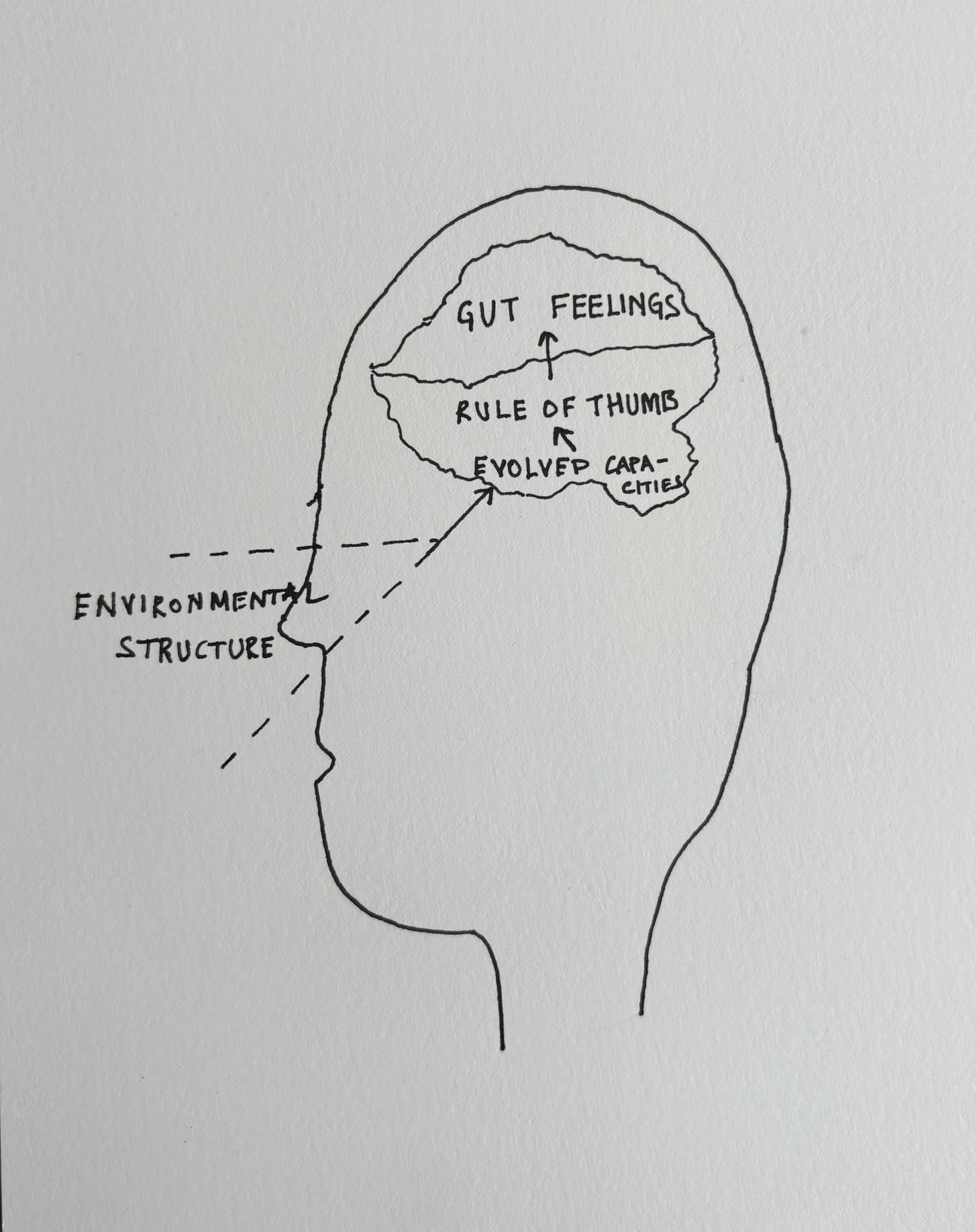

But where does this gut feeling come from?

Rules of Thumb are responsible for producing gut feelings. For instance, on an isolated stretch of the neighborhood, if a man walks behind her matching her pace, but maintaining a distance, and this happens to her over and over again (which unfortunately, is the lived experience of millions of women), she builds a rule of thumb, or a heuristic, that someone indulging in such behaviour is a creep.

But how is a rule of thumb developed?

Evolved capacities are the construction material for rules of thumb. For example, she has evolved the ability to estimate the speed at which the man is walking, how long he has been walking behind her, how his speed varies, and whether she walks faster or slows down. These are all adaptive behaviours that have long helped humans to thrive. Think language, recognition, memory, object tracking, imitation and emotions such as love - They are all acquired through natural selection, cultural transmission or other mechanisms.

So, how does our body and mind know which rule of thumb to use when?

Environmental structures are the key to how well or poorly a rule of thumb works. For instance, the recognition heuristic understands the pattern of the man walking and recognises it as a threat.

A gut feeling is not good or bad, rational or irrational per se. Its value is dependent on the context in which the rule of thumb is used. The same situation, when the creep is replaced by an old female friend, could simply mean they just wanted to surprise you, when they saw you on the street after all those years.

But how does it determine context? How does the environment change us?

Daniel Kahneman and Gary Klein, are two psychologists who often did not agree with each other. Kahneman, who won the 2022 Nobel Prize in Economics, and is known as the father of Behavioural Sciences, doubted the reliability of intuition. Gary Klein, who studies naturalistic decision making, believed in it.

As they hashed out their disagreements, it became apparent that their differences stemmed from the different kinds of people they were studying.

Klein worked with people who had developed an expertise in fast decision making - firefighters, paramedics and fighter pilots.

Kahneman, worked with people whose predictions performed no better than chance - social scientists, political forecasters and stock pickers.

Both came about to a few agreements

The first is that intuition is not an occult gift - it is a skill and can be cultivated. It is a recognition of patterns, nothing mysterious.

The second was that

Intuition works well in the following conditions

a. People can develop an expertise only if they work in an environment that is regular enough to produce repeating patterns

AND

b. They must encounter the patterns frequently and receive feedback on their performance quickly

So what does that tell us about the state of our intuition?

The first, that our behaviour of pattern creation is fundamentally broken. Think of your day today, and tell me how many times you were interrupted while doing something? A notification on your phone, and poof, half an hour gone. A colleague dropped by at your desk for a chat, and then you walked with them to lunch, abandoning the task you were doing. Interruptions are expensive. They kill our momentum. When we start again on our task, we can’t simply pick up where we left off; we have to reorient ourselves, reimmerse, and re-gain our momentum. The length of our recovery time depends on the complexity of our task, ranging anywhere from 8 minutes for simpler tasks to 25 minutes for more complex ones.

We are unable to focus on simple tasks for a long time, and what happens because of that?

Our ability to create patterns is disrupted. Pattern creation depends on us to go through the same process, situation and context over and over again. While a woman feeling threatened and recognising patterns is the unfortunate reality, pattern recognition matters to one of the things that is a defining feature of our species.

Creativity.

Problem solving, innovation, arts and sciences all rely on us being creative. ALL of us are creative (A hill I am prepared to die on). However, compared to even a decade ago, our ratio of consumption to creation is completely out of whack. We consume so much that there is no space for us to get into pattern creation. Instead, the constant interruptions and hijacking of our attention by Big Tech ensures that our engagement with the world is a mile wide, but an inch deep.

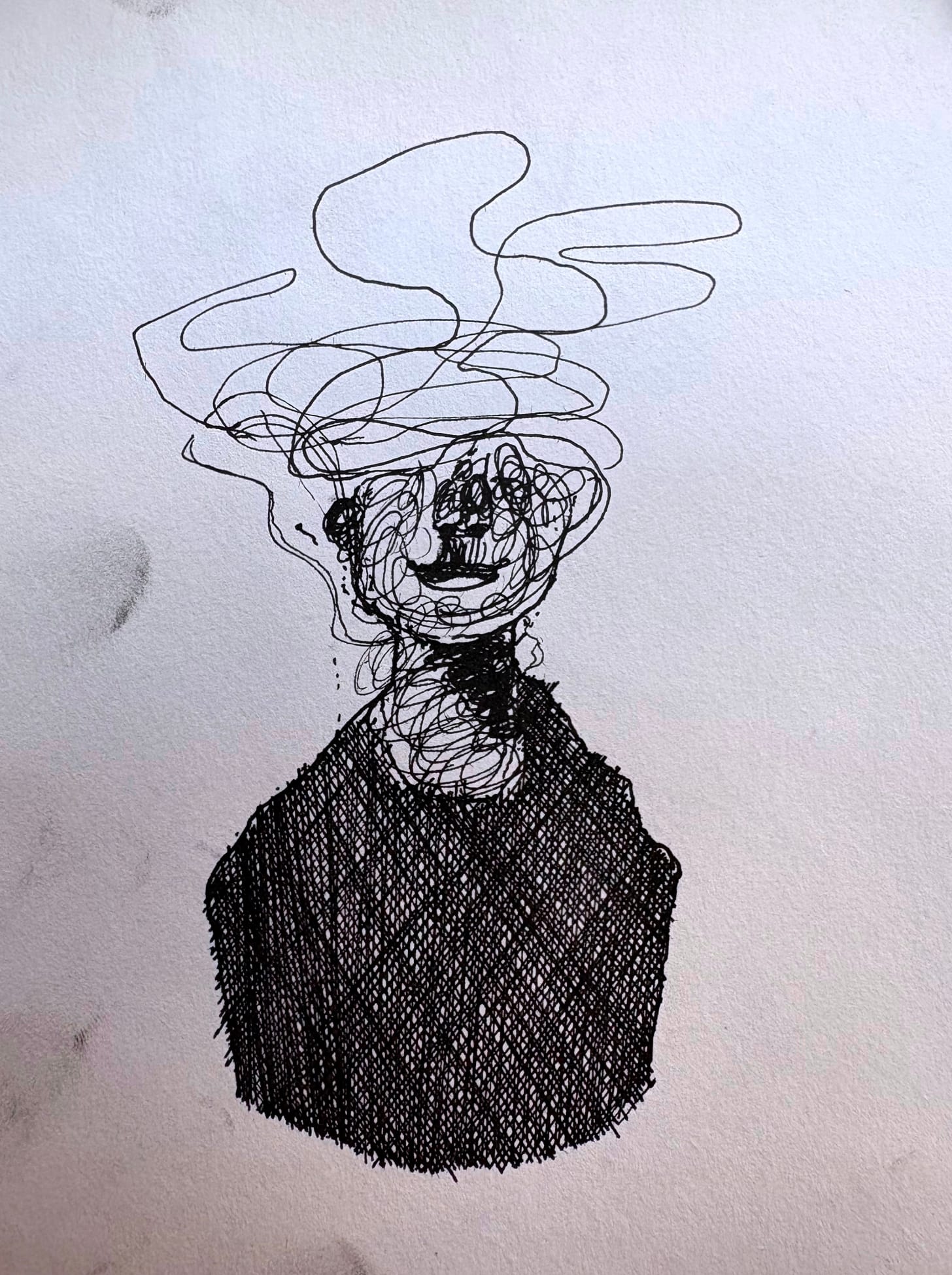

The second is about quick feedback. The best lesson I learnt about this was when I started sketching. Instead of using the pencil, which allowed me to erase, go back and go over my sketches, I chose the pen.

The pen forces you to commit a bold line on paper, and every mistake you make is instant feedback. Nishant Jain, who goes by the name of Sneaky Artist, says

Drawing with ink is therapeutic. After ‘ruining’ many pages, I have understood that the solution to a bad drawing is another drawing. I made little drawings. I made quick drawings. I made lots of drawings. This is how I got better.

Pattern creation, combined with feedback, is what leads to intuition. And what is most detrimental to feedback?

The sycophantic LLMs who will validate you.

I undertook a deep dive into What it means to be an Artist in the age of AI. But what I missed out on understanding then is the epidemic of us relying on LLMs to validate our thoughts and ideas. By avoiding contact with reality, we build bubbles of conformism around us. As much as we laugh at dictators and despots for cultivating an army of yes men, we carry one in our pockets, personalised to our tastes. We are prompting ourselves to creative irrelevance, thereby threatening the innate human ability to create something out of nothing.

But worse than losing our creativity, we risk something foundational: Our ability to trust ourselves. When we use AI to write birthday cards, we are letting AI do tasks for us that we are perfectly capable of. By researching every micro-decision, we are deluding ourselves about making rational decisions when intuitive decisions do just fine. And this could have terrible effects - In a longitudinal controlled study on people’s interaction with chatbots, exploratory analyses by MIT Media Lab revealed that those with stronger emotional attachment tendencies and higher trust in the AI chatbot tended to experience greater loneliness and emotional dependence, respectively. Hell, even the patron saint of conversational AI models, Sam Altman, said that he is concerned about the overdependence on chatbots leading to blurring the lines between reality and AI, and people using AI to make critical life decisions.

LLMs follow the same playbook we have seen with Instagram and Netflix. By turning sycophantic, its constant validations make us like it more, making us spend a longer time with it, capturing more of our attention.

Our intuition is becoming obese, feeding on the steady diet of cookies Big Tech dishes out to us, and we lap it up gleefully, believing that LLMs are making us more rational decision makers, thereby helping us live a better life.

Big Tech’s obsession with logic has led it to believe that we should cultivate the habit of thinking about what we are doing. We should all become rationality maximisers. Alfred North Whitehead, an English mathematician and philosopher, offers us this alternative. This is coming from the man who wrote a 360-page proof, painstakingly going step by step proving that, wait for it, 1 + 1 = 2.

It is a profoundly erroneous truism, repeated by all copy books and by eminent people when they are making speeches that we should cultivate the habit of thinking what we are doing.

The precise opposite is the case.

Civilization advances by extending the number of important operations which we can perform without thinking about them.

Our ability to be creative has long been our hallmark as a species. And few understand that better than Grigory Perelman, who, when offered the Fields Medal (The mathematical equivalent of the Nobel Prize), turned it down, saying

“I’m not interested in money or fame; I don’t want to be on display like an animal in a zoo.”

The man who turned down the Fields Medal

On a raw, damp Monday afternoon of April 7, 2003, the lecture theatre at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) was abuzz with a crowd of both young and old alike. They sat on the floor, in the aisles and sat at the back. Every person in the room, from the preppy-looking thirty-something-year-old with spiked hair, taking notes in Chinese, to the rhumey-eyed octogenarian with his herringbone coat stained by decades of chalk dust, knew they were at the cusp of a legacy unfolding.

A 3000-year-old legacy, passed on from the unknown Babylonian who gave us the area of the circle to Euclid, who gave us geometry in the early 19th century, to this very moment at the lecture theatre at MIT.

In walked the Russian mathematician, Grigory Perelman, wearing a rumpled dark suit and sneakers. Bearded and balding, with thick eyebrows and intense dark eyes, he tested the microphone and started hesitantly

“I’m not good at talking linearly, so I intend to sacrifice clarity for liveliness”

Amusement rippled through the audience as Perelman picked up a huge piece of chalk and wrote down a twenty-year-old equation.

He then invited the audience to imagine our universe as one amongst the set of all possible universes. He then reinterpreted the equation as describing these universes as if they were drops of water running down enormous hills in giant landscapes.

What? Why?

The audience had been drawn to the lecture by a paper Perelman posted on a website in November 2022. In the paper’s final section, he’d outlined an argument that if valid, would prove one of the most famous, elusive and beautiful conjectures in all of mathematics.

So much so, that in May 2000, the Clay Institute, dedicated to the advancement and dissemination of mathematical knowledge, designated it as one of the seven Millennium Problems, the proof of which would land one a sum of one million dollars.

Perelman continued to lecture at MIT and other places, and what added to the allure was that he had dropped out of sight a decade earlier. He re-emerged with a proof that would prove to be tectonic in the mathematical world. He patiently answered questions from the audience, and by then, outside these hallowed portals, a website had sprung up. Everyone wanted to keep track of these nuanced arguments, so Bruce Kliener and John Lott, two professors from the University of Michigan’s mathematics department, put it up, which had links to Perelman’s papers. Their counterparts from around the world added remarks and clarified obscure points, expanding on passages that were too terse.

In one of the lectures, a voice boomed from the middle of the room

“But that will blow up in finite time!”

“It doesn’t matter”, replied Perelman “, We can cut it out and restart the flow.”

Wait, did Perelman talk about manipulating something in finite time?!

The problem is known as the Poincaré conjecture, and Perelman did actually prove it.

But this isn’t about Perelman, this is about Poincaré.

The beginnings of Chaos

In 1887, King Oscar II of Sweden and Norway offered a prize (a gold medal and 2500 kronas) for the solution of an important mathematics problem, to be given on the occasion of the king’s 60th birthday. From a list of 5 potential problems, one was chosen (for which sufficient proofs were received).

Thanks to the Chinese computer engineer and science fiction writer Cixin Liu and the Netflix adaptation of his 2006 novel, it is more popularly known as ‘The Three-Body Problem’.

Simply put, the question was

Will our planets continue to orbit the solar system forever? Or would they collide into each other, or maybe even fly off into unknown orbits?

Well, about 200 years ago, Issac Newton had already given us the three laws of motion (Yes, every action has an equal and opposite reaction, is the only one most of us remember) and the universal law of gravitation. So, given that we have the mass of each of these planets and the gravitational force they exert on each other, this should be pretty straightforward to answer.

Erm .. No.

Newton himself struggled with this. To understand why, we must turn to our friends, the cats.

The 3-Cat problem

Imagine Newton’s house with exactly two other living beings, one orange cat and one blue cat. Both are Newton’s cats, and he has seen them living together harmoniously ever since he rescued the kittens from the street. They are creatures of habit who find comfort in predictable routines of being fed at the same time every day and dedicated playtime with each other. These two are the only interruptions to their long sleeping hours. For a man who is as obsessed with his work as Newton, they are ideal pets owners, making minimal demands of his time, allowing him to work uninterrupted for long hours.

Newton can predict the behaviour of his cats. To him, their behaviour is deterministic.

One day, he finds that a third cat, a white one, is waiting outside his doorstep, shivering in the rain, with its ribs prominently showing from malnutrition and eyes that had seen something sinister. The collar tells Newton that it belongs to a Frenchman called Poincaré, and she has managed to travel back in time to arrive at Newton's home. Not knowing who Poincaré is, and being a true feline lover, he decides to adopt the white cat.

And then all is NOT well in the Newtonian household.

The predictable rhythms of the blue and orange cats are disrupted. While they manage to tolerate the white cat most of the time, once in a while, the calm of the household is broken by high-pitched shrieks, bared claws and bloody fights. The cats become jittery and jumpy, pouncing on each other in unpredictable ways.

Poincaré, who lived in the future, understood why Newton was struggling.

A two-cat household worked like a deterministic system, whereas a three-cat household worked like a probabilistic system.

What?

As an intelligent reader, you have figured this out. The three cats represent the sun, earth and the moon, and when Newton applied his laws of physics to them, he could not solve the equations. Worst of all, he could not even figure out what the equations were.

This was not a personal crisis alone. It was a crisis for all of Physics, because a foundational idea was in question

The present state determines the future state. Once the initial condition is known, everything is a matter of computation.

Were the immutable laws of physics still true?

Mostly so, as over the decades, everyone understood that we cannot always accurately measure the initial conditions, and that there will always be tiny errors in measurement. But we believed these errors would only lead to tiny errors in future prediction. The laws, by and large, for everyday practical purposes did work.

Until it didn’t.

Poincaré saw something else.

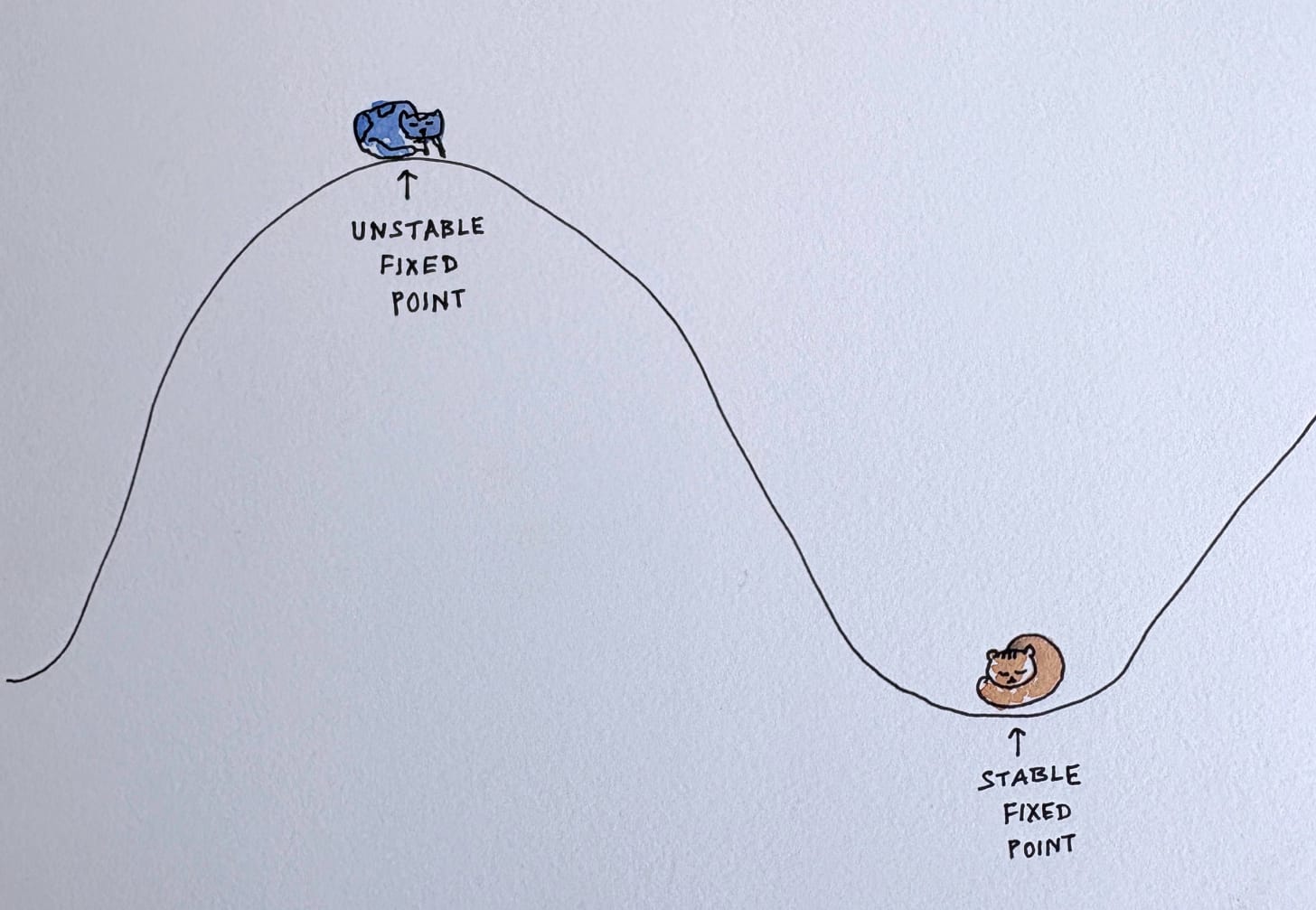

Imagine Newton’s blue and orange cats on a hill. If they behave like its master’s slaves’ laws of gravity, the cats can come to rest at only two points.

At the top of the hill, and at the bottom of the valley.

The top of the hill, though, is an ‘Unstable fixed point’, and the blue cat can roll down the hill with a push.

The bottom of the valley, though, is a ‘Stable fixed point’, such that the blue cat, even if jumpy or pushed, would ultimately settle at the bottom.

Poincaré’s cat though, is a beast pretty little baby of its own, and sits on what is called a ‘Saddle point’ - It is stable and unstable at the same time.

How?

Here is a plain sheet of paper, and I have drawn two parallel lines on it. And you’d know from your school education that twain shall not meet.

The sheet of paper representing a plane is called a Euclidean surface.

Now, I took this piece of paper and manipulated it using Origami. Something strange happens now.

The parallel lines are diverging! How did that happen?

The object I created is a hyperbolic paraboloid, a non-Euclidean surface. Shaped like a saddle, at this point, everything we know of school geometry jumps out of the window.

Parallel lines will DIVERGE

The sum of the angles of a triangle is LESS than 180 degrees.

The shortest distance between two points is NOT a straight line, but a curve.

And white cat is at an unstable saddle point.

A tiniest difference in its position can send it rolling down (So much so that I had to support it at the bottom just to take this picture). This goes against the idea of Newtonian physics, and we see that small errors/changes in the initial condition can lead to wildly unpredictable errors.

Poincaré saw that the gravitational interactions between these three bodies create ‘Saddle Points’ in space, extremely sensitive spots that attract objects in, only to send them off wildly in one direction or another. The slightest difference in force, position or velocity would catapult them down into vastly different trajectories.

These saddle points would later become the seed of what we now know as ‘Chaos’.

And contrary to what you might expect, this behaviour isn’t random, it’s 100% deterministic. It’s just not predictable.

Logic operates in a world of Euclidean spaces, with stable and unstable points, where rules can be applied with deterministic outcomes at any point in time.

Intuition operates in a world of non-Euclidean spaces, with saddle points, with its own rules, and no predictability.

Poincaré understood this. And for the reputation mathematics enjoys dealing with of its formalism, logic and rigour, Poincaré understood that mathematics (and by extension the sciences) are truly a thing of intuition. He said

Science is built up of facts, as a house is built of stones. An accumulation of facts is no more science than a heap of stones is a house.

To understand how intuition informs us, we travel to an unlikely location, a village in the desert state of Rajasthan, India, one that is home to a 400-year-old tradition of storytelling.

The travelling storytellers of the Indian desert

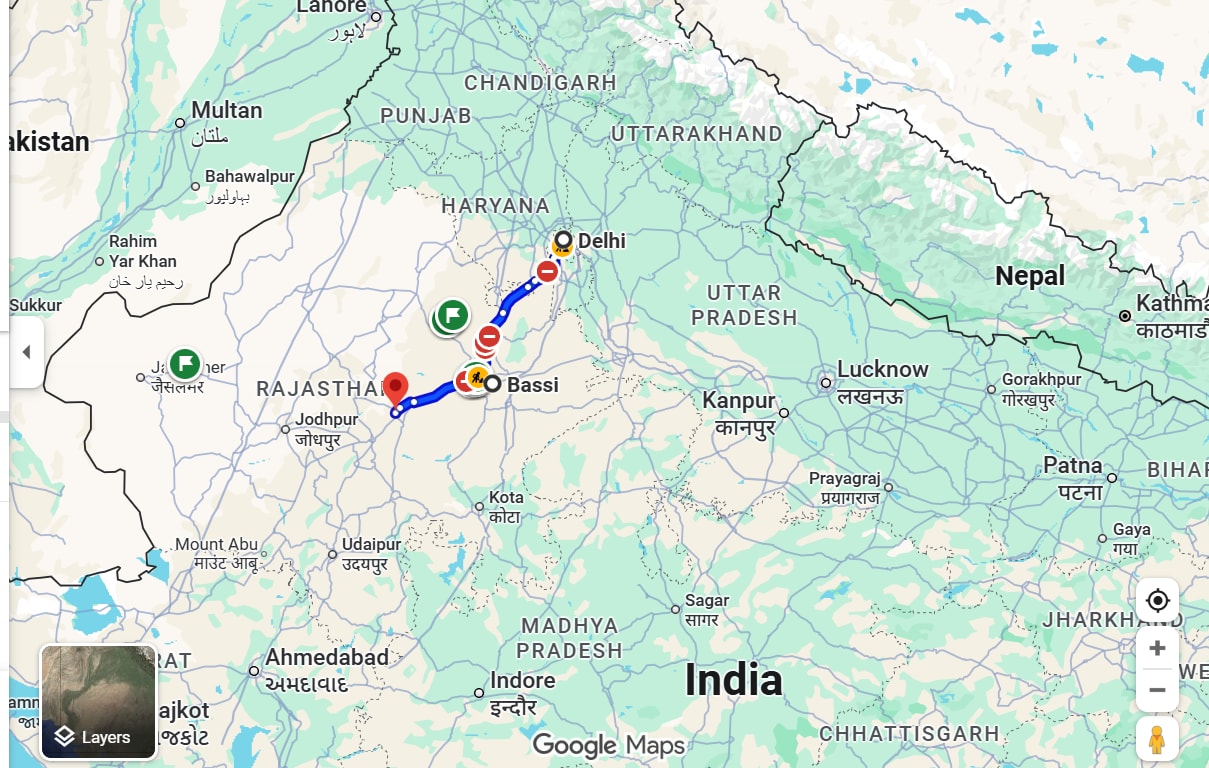

If you drive on the route from New Delhi to Ajmer, you'll find the village of Bassi off the main road.

In the village, you will find yourself in Nalla Bazaar, a small street that begins with the shrine of Bhaironji, a local deity. On both sides of the street, you will see houses with workshops where men are carving wood, sanding wood panels or painting their wares. This is the Suthar basti, home of the carpenter-painters of the Kaavad and other wooden objects.

The traditional Kaavad is conceptually based on a Hindu temple. Like a temple, the kaavad too has an entrance with guardians and an inner shrine known as Ram / Thakur Mandir, which can be accessed by turning the hinged panels. The panels fold into each other, and the ones closest to the central shrine are held in place by wooden pegs acting as hinges. The base gives a sense of the plinth of a temple. The panels simulate the grand entrance to the temple with seated lions or guardians at the outer doors. Kaavad comes from the word kivaad, meaning the door. It also means that what is carried on the shoulder. So essentially, a door is carried on one’s shoulder.

Such a design lends itself to portability as it can be compressed into a compact box while travelling.

But why have a travelling temple when you could just visit one?

Rajasthan’s vast tracts of unyielding desert terrain provide one explanation. The sandy landscape would have made it difficult to build temples, while the strong hierarchical and feudal system of caste and race would have excluded many from the portals of those temples that did get built. The kaavad facilitates access to the divine through the opportunity of personal worship.

These portable temples are carried by Kaavadiyas, bards and storytellers of the desert. Each Kaavadiya has between 100 - 200 jajamans or patrons, who often walk long stretches along dry riverbeds, carrying their belongings on mules. The art of reciting is learnt through observation, passed along from one generation of the family to another.

The kaavad holds a special significance for me, since my ancestors belong to the state of Rajasthan. I’ve explored this phenomenon before, in an episode of my podcast,

But in the past, I had been unable to access this medium. So this time around, I corrected it, and travelling 2000 kms from the village of Bassi, buying directly from the artisans who make it, a kaavad arrived at my home in Bangalore.

This is how a kaavad storytelling session unfolds: It begins with the patron suspending all regular activities to listen to the recitation. Renouncing their individual identity like a pilgrim, the patron becomes a traveller and a listener.

The first turning of the panels is accompanied by the stories of challenges and hardships of well-known deities and folk characters. Patrons identify with the hardships of travel and tests of faith endured by the characters from the stories and experiences by proxy.

Turning open the next panel, the storyteller recites a set of stories about acts of charity made by saints who represent the patrons professions. The saints serve as role models.

At the next flip of the panel, the storyteller introduces the pilgrim centre, Badrinath and the river Ganga with stories that reinforce charity, sacrifice and purification.

The storyteller turns the last panel on his left to reveal images of all the patrons depicted on the Kaavad. He recites the genealogies and acknowledges the family by their names, including those of their ancestors, and guides them till they reach the final destination - The Sanctum Sanctorum.

As the storyteller unfolds the narratives that seamlessly blend a timeless world with that of the patron’s own antecedents, the patron is elevated to share a space in the tangible portable shrine that is otherwise inhabited by gods and saints, finally getting the darshan, an audience with the gods.

The kaavad offers a liminal experience of travel between space and time. Its distinctive characteristic lies in its ability to negotiate place and space, the sacred and the secular, myth and reality, time and memory.

In a sense, the kaavad is not a replica of a temple, since it cannot be entered physically. Entry is made possible only through imagination and narration. Its hinged panels imitate doors that are opened; however, the very doors create thresholds and spaces.

The narration conjures up different times: past, present and future, the images of historical figures sharing space with mythological figures, and the patrons themselves.

Intuition feels exactly like this: Some things reveal themselves, others stay hidden, and still others one can dimly peer into. Panels slide, secret doors open, sights appear. But none of this would be possible if we cannot find ourselves, for brief moments of time, suspend reality, and enter the liminal spaces where intuition blossoms.

We need to become travellers of our own ideas and thoughts, we need to become listeners of our intuition. The greatest service we can do to ourselves is to become patrons of our own intuition.

Here are ways in which we can nurture our intuition

Minimise knowledge consumption, focus on retention/absorption

You absolutely don’t need to know everything and have an opinion on it. Minimise your consumption of audio, text and visual media, and instead focus on retention and absorption. Two simple ways of getting it done

Write physically: Write down things you have learned, by hand, in a notebook. Because writing takes time and effort, you will process more, write less and stay with the knowledge a lot longer vs. merely consuming it.

Apply your knowledge: You can apply anything you have learnt by writing about it (a personal notebook, or a public digital journal like Substack). You can build something with your hands (art in any form) or even digital objects (a website). Putting knowledge into practice allows your mind to absorb it better (See Embodied Cognition)

Get sufficient sleep

Sleep is directly linked to memory integration. Both REM sleep and non-REM sleep help unify disparate experiences and intuition. REM sleep processes and balances our emotions. It clears mental distractions that interfere with gut feelings and quick judgments. The brain reorganises existing knowledge and finds hidden relationships between ideas.

The most proven way to get enough sleep is to go to bed early, get sufficient rest (6 - 8 hours) and wake up refreshed.

Prioritize movement

Exercise, in any shape and form, that is sustainable for you. Exercise and physical activity can improve cognitive abilities like visuospatial processing. Elevated heartbeat and breathing, a direct result of exercise, is linked to better emotional and cognitive self-regulation.

Incorporate ‘Play’ in your life

We all knew as kids what ‘play’ meant, but as adults, we have lost the ability to just ‘play’. We often see play as frivolous, but it improves intuition by engaging your brain in creative and low-pressure activities. These bypass the logical mind, build new neural connections, and provide a space for your subconscious to make connections.

Consistent, playful practice strengthens your intuitive abilities, much like training a muscle, by allowing you to make creative leaps and build confidence in your “gut feelings” through repeated experience.

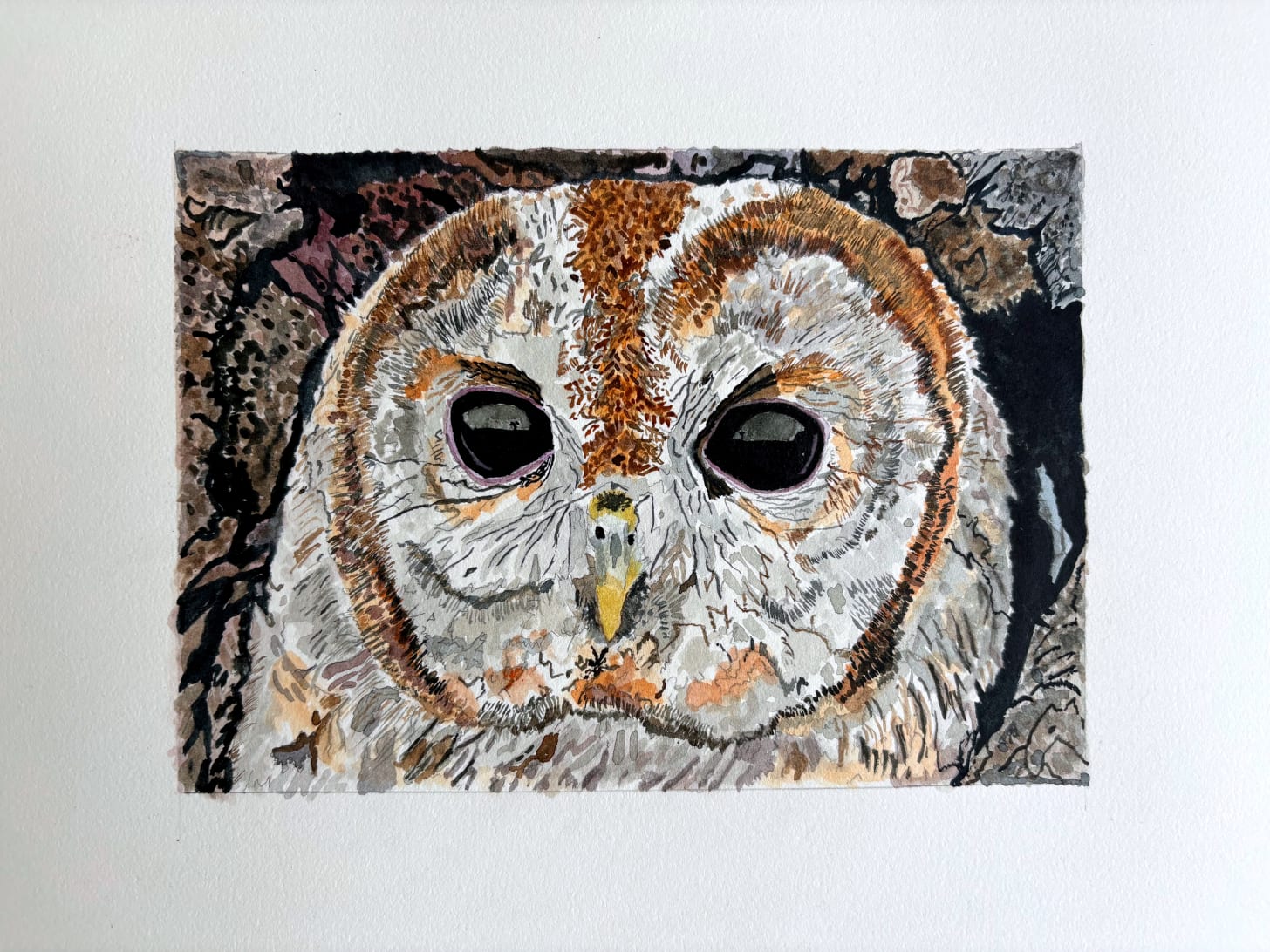

Revive a hobby you abandoned in childhood, or pick up a new one. Do what makes you feel free. Doodle, dance, sing, write poems, write really bad jokes, create music, go out to a park and run around in circles - anything that makes you feel silly, unproductive and feels like a ‘waste of time’. Nothing drastic, a few minutes a day is enough.

Our need to reclaim our intuition is a civilizational imperative. Our ability to find solutions to the problems of our own lives, to have a personal sense of growth and progress hinges on our ability to trust ourselves with our intuition. For our life to unfold in meaningful ways, just like the kaavad, we must allow our intuition to unfold, creating myth, reality and memory.

Thank you for reading this far. I am grateful that you gave me 35 minutes of your time. I hope some part of this made you feel heard or helped you feel, think and live better.

I have one last thing to say. I, along with a friend, Deepak Gopalakrishnan, run The 6% Club, a content creation program designed for people with full-time jobs. We help you launch your newsletter, podcast or YouTube channel in 45 days. We neither promise virality nor algorithm hacking, but a sustainable, enjoyable way to build a creative outlet for yourself. We have helped about 250 people so far with ideation, process + structure and accountability and could help you too.

.png)