I was recently interviewed by Realtor.com about the game Monopoly, which inspired today’s piece.

Imagine you are invited to play a sixteen-player game of Monopoly. Arriving in a party of four, you discover that four other players started without you and all the property cards have already been snapped up. In such a rigged game, you would have almost no chance of getting on the “property ladder” and would spend most of your time paying rent to other players until you inevitably go bankrupt.

You bring this up with the original players, who agree that the current scenario isn’t fair. After all, when they started playing the board was blank, and all the properties were still available and cheap. One of them proposes a solution—he pulls out another Monopoly game board. With a little duct tape, a sharpie marker, and a few house rules, an expansion set is made. The board is now twice as big, with twice as many land parcels, all available on the same cheap terms the original players enjoyed. Go west, young man, and seize your manifest destiny!

With the playing field somewhat leveled, all it takes is a little luck and a few shrewd deals for you and your friends to become property owners. Just as you complete your monopoly over “New Park Place” and “New Boardwalk”, there’s a knock at the door and four more players arrive. Another game board is found, more sharpie and duct tape is employed, and the new players settle in.

All is well and good until a another cohort of players joins in a few hours later, and someone goes back to the closet to look for another game board. No such luck—there were only three in the house. The original players shrug their shoulders, and the new players try to make the best of the situation. Despite their best efforts, the last players to join are quickly eliminated, and the Monopoly game ends in the traditional way: with everyone yelling and shouting at each other.

In case you couldn’t tell, this is a metaphor.

The Monopoly game is the American housing market, and the player cohorts are generations. The game boards represent frontiers—useful land that can still be had for cheap. Whenever productive land in America becomes scarce, our solution has always been expansion.

The first frontier consisted of the original thirteen colonies, as settlers left England for the New World. The second frontier was westward expansion: the Louisiana purchase, the expulsion of the Indians, the Oregon Trail, the Mexican-American war, the Gadsden purchase, and all that Manifest Destiny stuff. This created genuine and lasting opportunity for not just the original English settlers, but also the many waves of immigrants from all over the world, who greatly improved their station by claiming a homestead of their own.

That said, frontier expansion was always an incomplete solution. For one, many people were excluded from the deal (Indians, slaves, and their descendants especially), and secondly, we eventually ran out of West. As the frontier closed, the Gilded Age dawned.

The term “Gilded Age” comes from a Mark Twain novel by the same name, meaning a false golden age, a shiny paper-thin veneer enshrouding a rotten core. The fundamental themes of this era were breakneck economic expansion, upper-class decadence, and pervasive political corruption. Henry George called this phenomenon of massive wealth marching right alongside massive want the paradox of Progress and Poverty, the title of his seminal work on the root cause of economic inequality.

Hailed by liberal, conservative, and libertarian economists alike (and despised by his rival, Karl Marx), George won over the hearts of workers worldwide and for a time led a movement that seemed unstoppable. When he died 200,000 people, a crowd 10% the size of New York City’s entire population, came to mourn him.

Yet as the twentieth century wore on, the movement he founded slowly faded away, and only now have its fallen embers begun to rekindle.

Why?

Scholars debate the root causes of the movement’s decline, but I have my own explanation.

First and foremost was chaos. The first half of the twentieth century was dominated by World War I, the Spanish Flu, the Russian Revolution, the Great Depression, and World War II, one right after another. The second half of the century was dominated by the Cold War and the ever-present fear of nuclear annihilation. Meanwhile, Capitalism vs. Socialism became the dominant economic frame, sucking up all the oxygen and leaving no room for the “third way” of Georgism, which served as a corrective to both worldviews.

The second and far more important factor was the automobile. Even as America’s borders stretched from sea to shining sea, one frontier remained unconquered—suburban land. Before, this land was of marginal value. Now with the advent of cars, cheap gasoline, and hefty investment in roads, it became possible to retain a high paying job in the city while living a life of comfort in the suburbs. America had found a third Monopoly board to duct-tape to the first two, and thus was born the famous “American Dream.”

As the problem the Georgist movement was meant to solve diminished, the movement went into decline. But as time wore on, the material conditions changed again, the old problems returned, and now modern writers have come to calling our own time the “Second Gilded Age.” As the western frontier’s close heralded the first Gilded Age, so the end of the automobile frontier announced the second. Henry George answered the call in his own time; that same trumpet awakens the movement today.

Had they the benefit of hindsight, Henry George and his followers should have anticipated the automobile frontier, because it’s evolution is squarely in line with their own theories. The chief one being the law of rent, borrowed from classical economist David Ricardo.

Let’s use this law to illustrate how frontiers affect the price of land, and why we can’t count on a fourth one to bail us out this time.

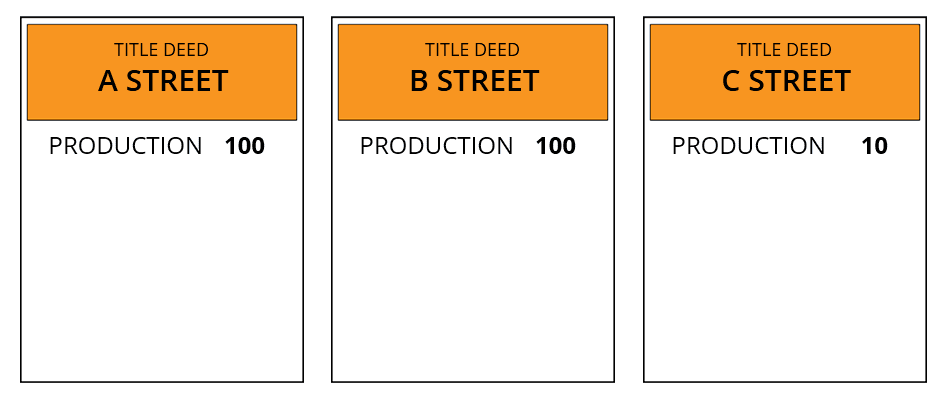

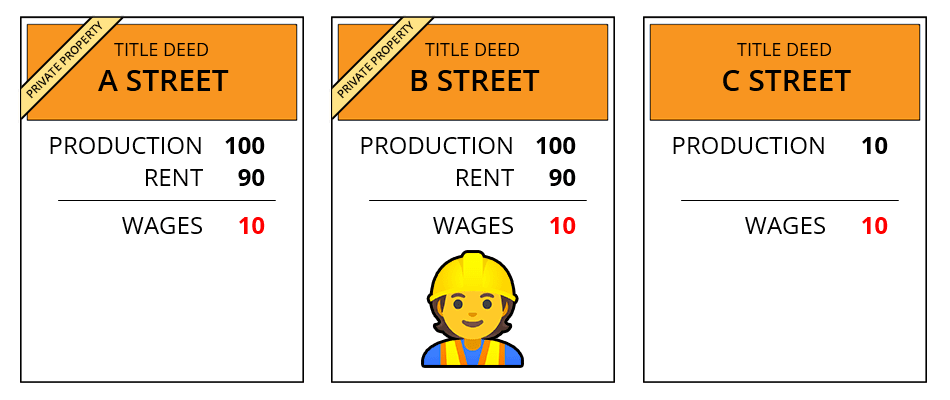

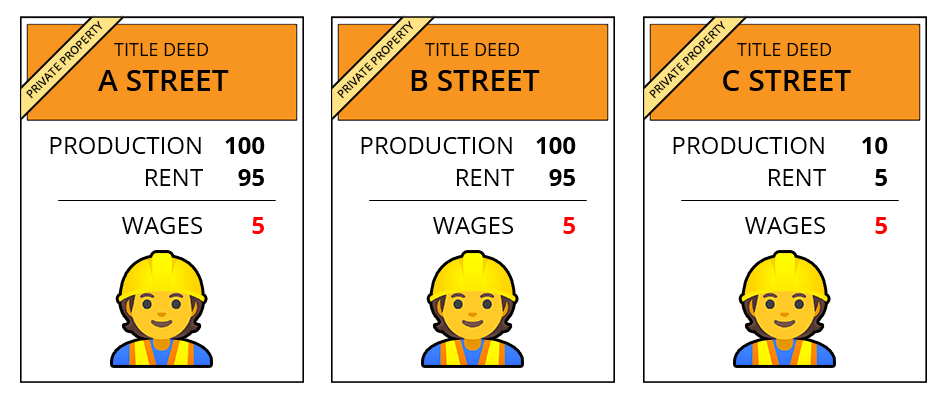

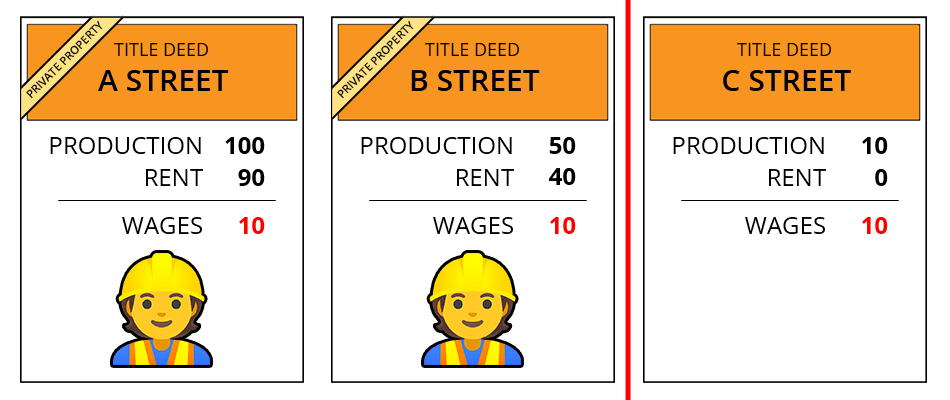

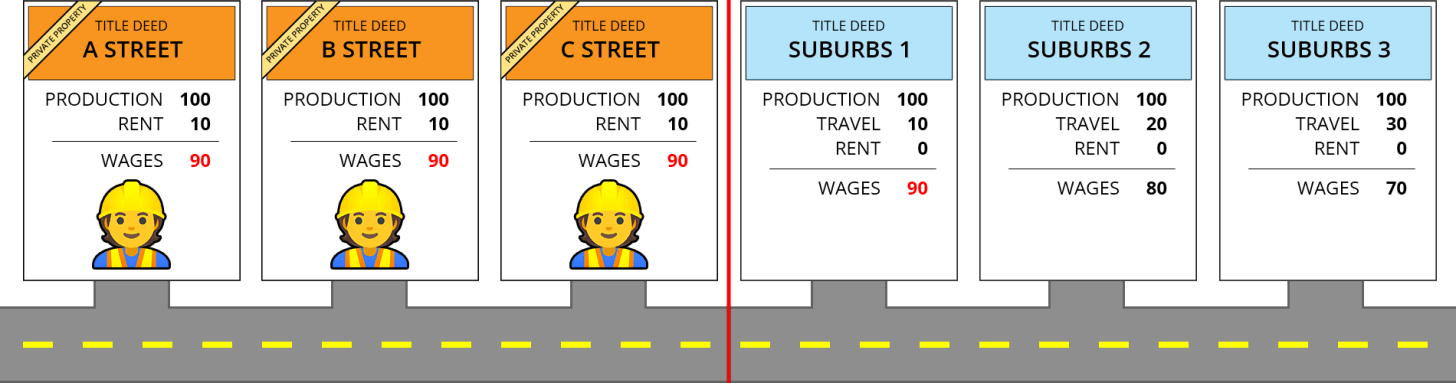

Imagine a city where everyone has to walk to work. In this city we have three locations available—a lot on A street, a lot on B street, and a lot on C street. Lots A and B grant access to the best jobs in town, but the only jobs you can get near Lot C offer low pay.

Which would be the best place for a worker to live if all land is currently free for the taking?

Obviously a worker would favor living on lot A or B, because each provides the best reward for the same amount of work:

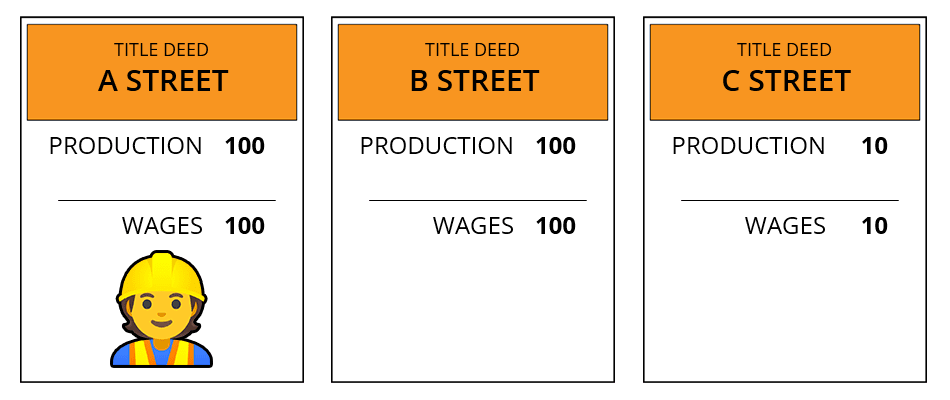

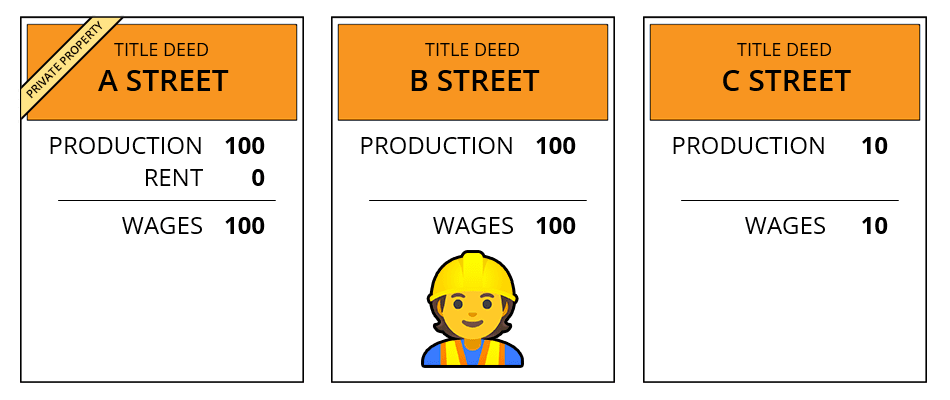

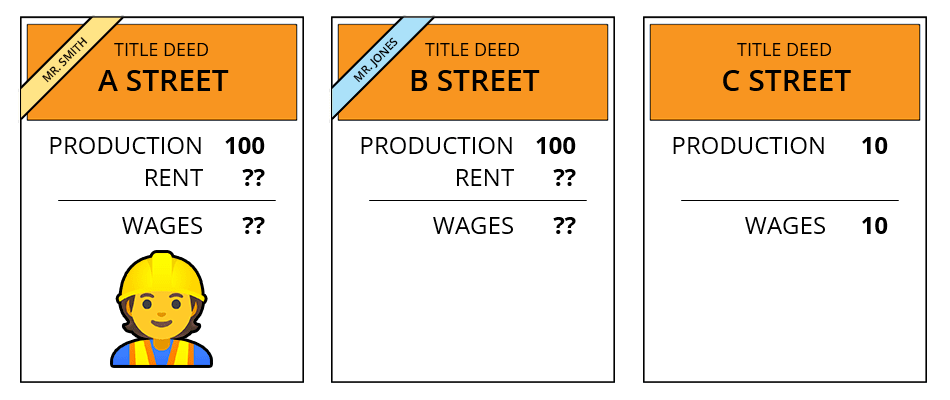

The next day, a landowner purchases lot A, makes no improvements, and requires payment for the privilege of accessing the location. How much can they charge in rent?

So far? Not a penny, because the worker’s best alternative to the landlord’s offer is right next door—lot B, which is equally productive, and available rent-free.

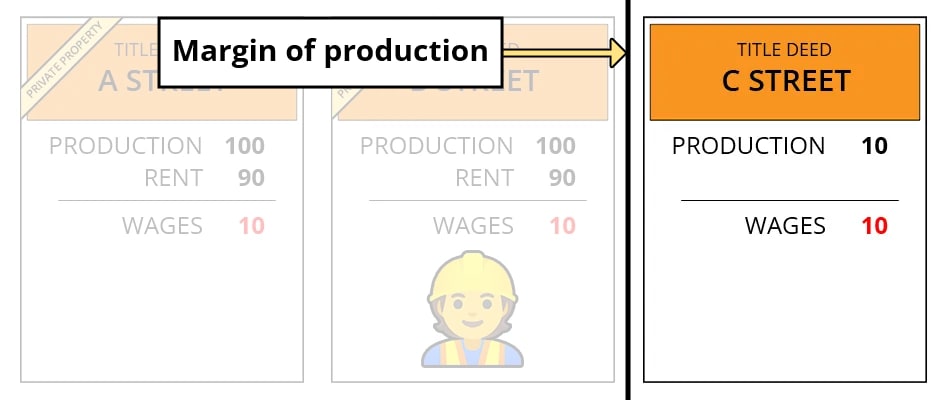

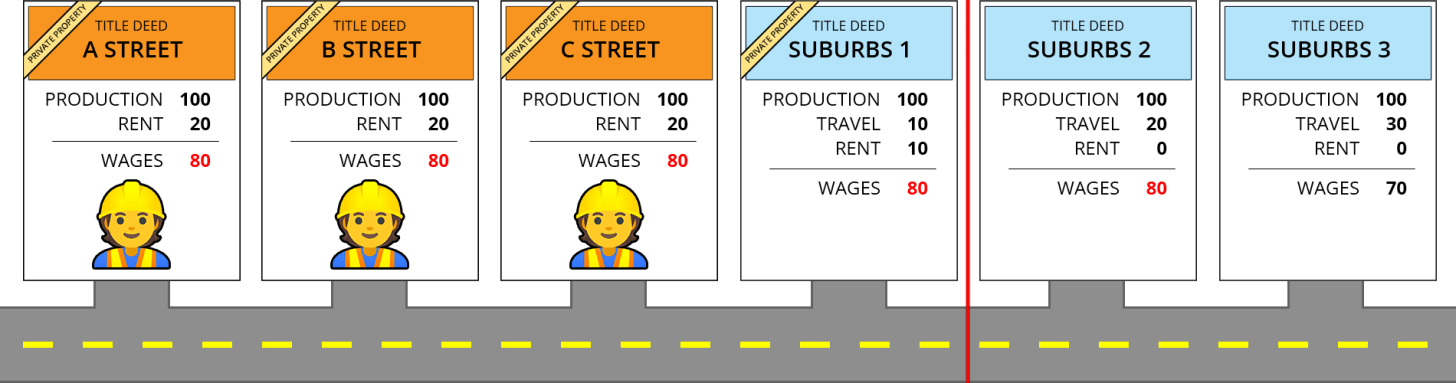

The landlord does not yet have sufficient leverage to charge rent. As soon as the landlord purchases lot B, however, the balance of power shifts:

Now the best rent-free alternative is lot C, whose yield is much lower. The landlord can now charge rent right up to the level that leaves the worker with as much money as they would get from working lot C.

That’s the basic version of Ricardo’s Law of Rent. The highest level of productivity that can be had rent-free is known as the “margin of production,” which in this example is 10. The margin of production drives how much landlords can charge in rent, all else equal.

Now, let’s look at some other factors that affect how much a worker pays in rent.

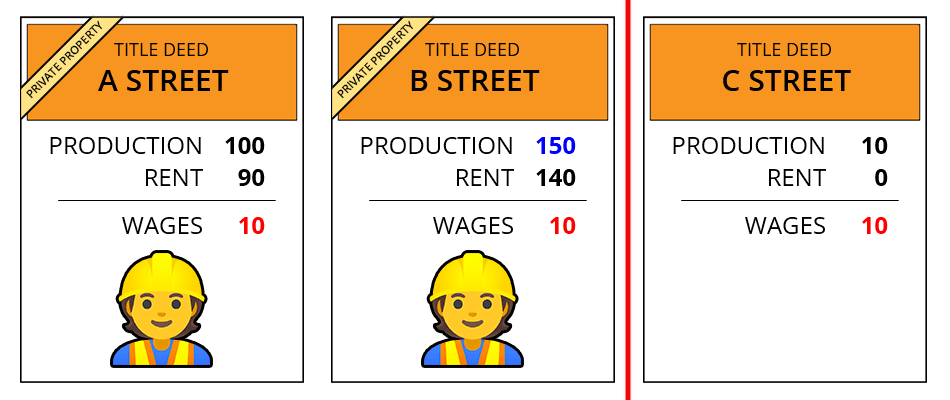

What happens if the tenant improves the property? To give us a concrete example, let’s imagine for a second that each lot now represents commercial space being rented. What happens if the worker improves Lot B, by, say, building a really nice building on it, that allows them to conduct more business?

The landlord raises the rent, of course!

This is because the amount that can be charged in rent is determined by negotiating power, and the worker’s best alternative is still Lot C—the margin of production—any improvements in the productivity of the land will in time find their way into increasing rents. This gives tenants little incentive to improve the value of the land that they work and live on.

What happens when multiple workers compete for a scarce number of valuable locations? Let’s rewind back to the scenario where only lot A is privately owned, and lot B is still available rent-free:

The worker is able to avoid paying rent and and keeps their entire paycheck. But what happens when another worker shows up?

Now somebody has to pay rent. Whoever is able to live at lot B will be able to enjoy the full fruits of their labor, but the next worker will have to resign themselves to either a low paying job accessible from Lot C, or pay an amount of rent on lot A that leaves them no better off.

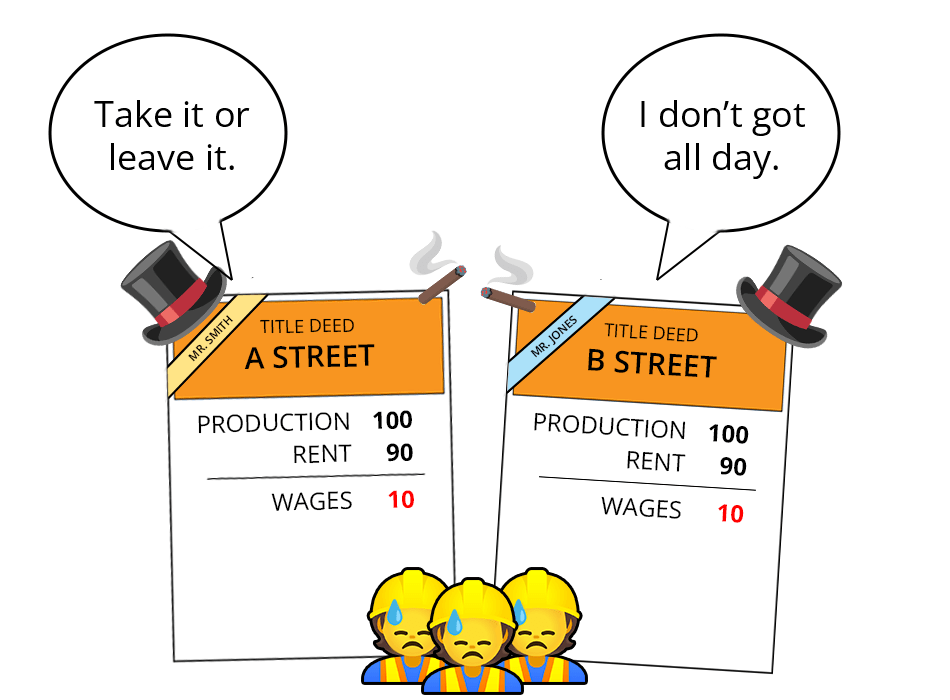

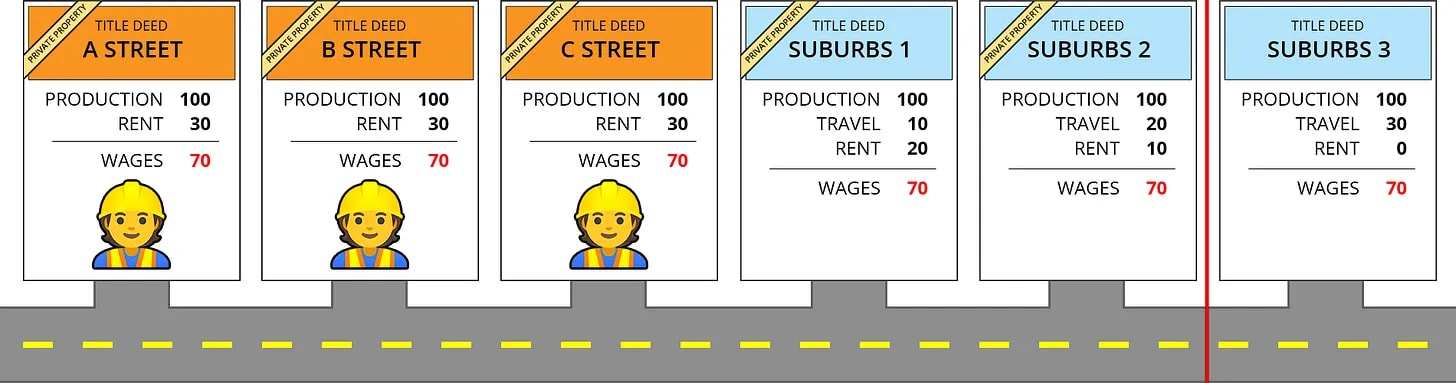

If a landlord proceeds to buy all three lots, and workers continue to move into the city, eventually there will be no rent-free alternatives left over. In this case, the landlord will be able to charge as much as the workers can possibly bear, right up to the limit of subsistence—the point below which workers will refuse to work at all. We’ll set that limit as 5 in these examples.

Land monopoly essentially forcers workers into one-sided competition with themselves, which, on average and in the long run, will steadily drive rents up. (Note that things change when you introduce skilled vs. unskilled labor—more on that in a minute).

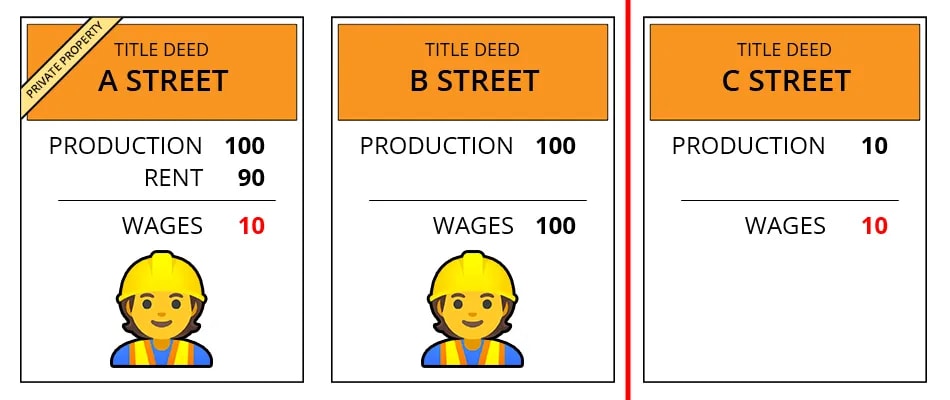

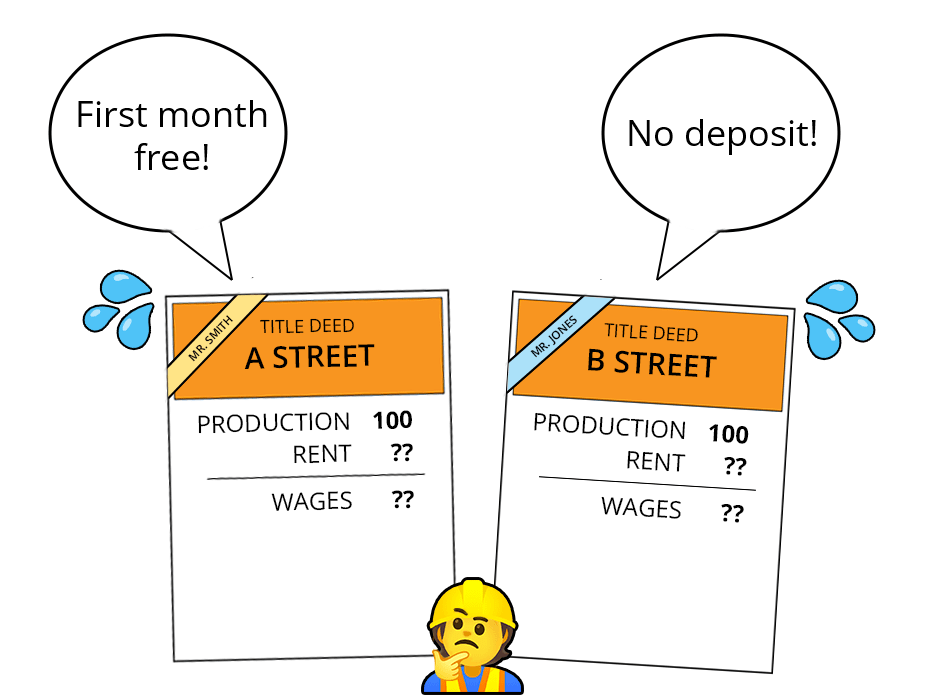

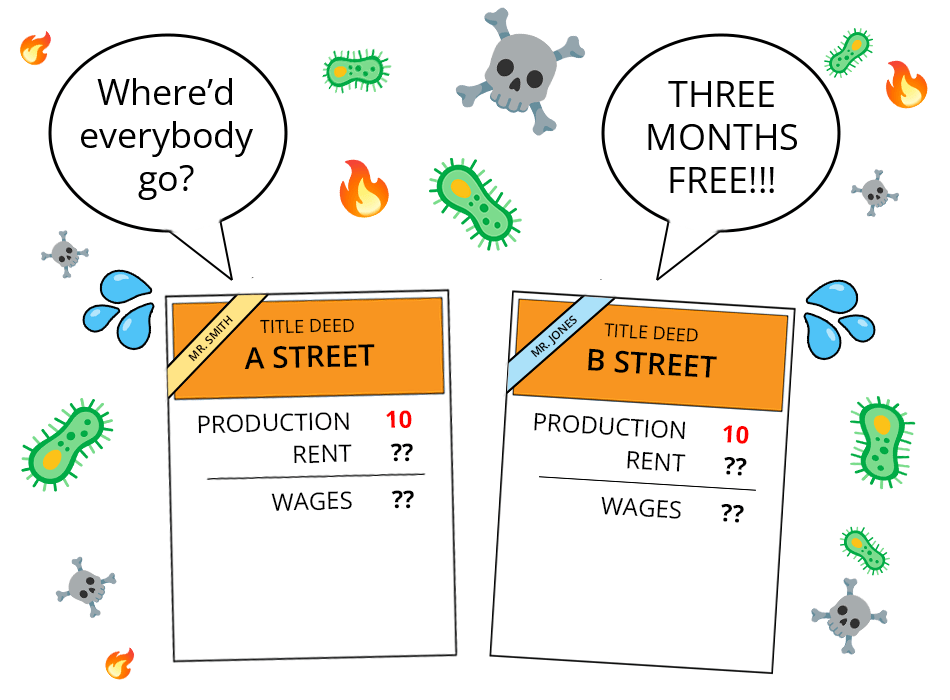

Landlords are actors in a free market, right? Aren’t they in competition with one another? Shouldn’t this drive rents down the same way competition between manufacturers has driven down TV prices? Let’s say lot A is purchased by Mr. Smith and lot B is purchased by Mr. Jones. What will the worker’s wages be?

Neither Smith nor Jones can charge more than 90 units of rent, because the worker’s best alternative is still lot C, which yields 10. That’s the maximum they can theoretically charge, but it’s not clear that either has enough leverage to get there as of yet. If there’s few prospective tenants, and in the absence of landlord collusion, a buyer’s market will force the two landlords to outbid each other, pushing down rent:

On the other hand, if population growth and a strong economy causes workers to flock to the city, landlords will soon have their pick of tenants, and can push rents right up to the margin of production:

Now, some will reply:

This doesn’t add up. I moved to the big city, and I made more money, not less, even after paying rent. Your model predicts that shouldn’t be possible, because any increase in a worker’s productivity will ultimately lead to increasing rents.

This is a keen observation. The key is that rent rises only in proportion to average productivity, and only over the long run. Your individual fortune depends entirely on where you stand in relation to the average worker.

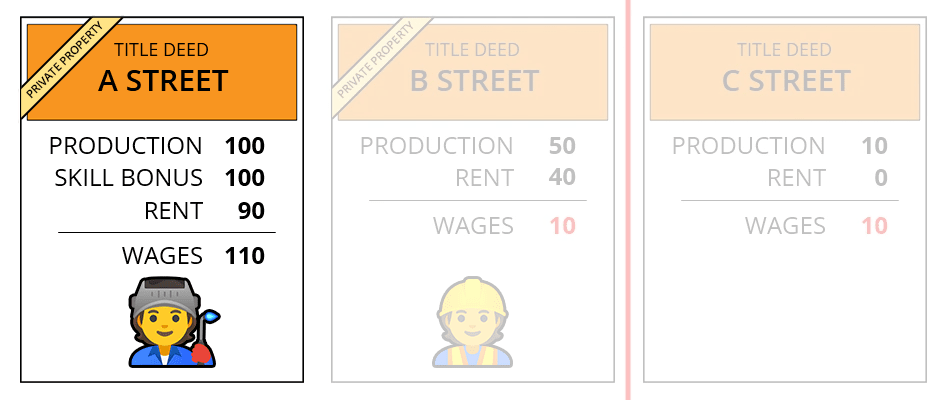

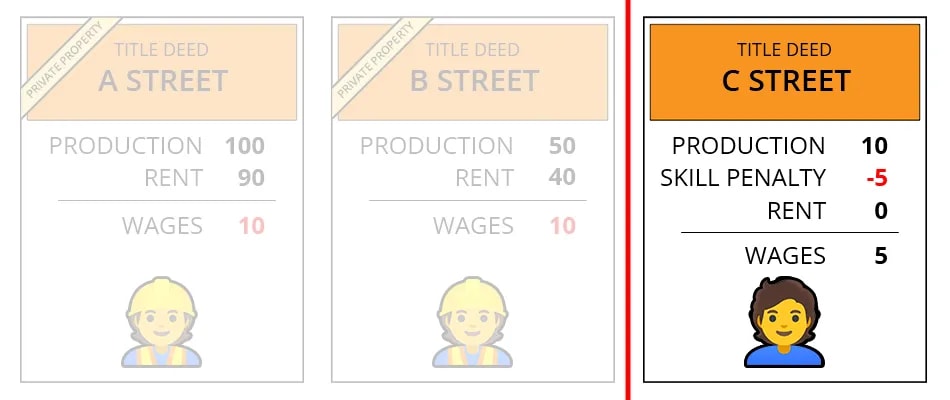

Let’s illustrate this quickly with another example, where our two best locations are worth 100 and 50 respectively, and our best rent-free location at the margin of production is worth 10.

Our “average” model looks like this—the best locations are more productive because of the locational amenities they have to offer, but as those locations fall into private hands workers must pay rent to access them. The average worker basically treads water.

The situation changes if you are above or below average. If you’re above average, the most valuable (and expensive) locations in the city are exactly where you want to go. Let’s model what happens if your skills, training, and education yield twice the productivity of an average worker:

You easily outpace rent, because rent is determined by average productivity rather than your own, and enjoy a large net income. You’ll also come out ahead in slightly less good locations, but you’d still prefer the best locations to maximize your income.

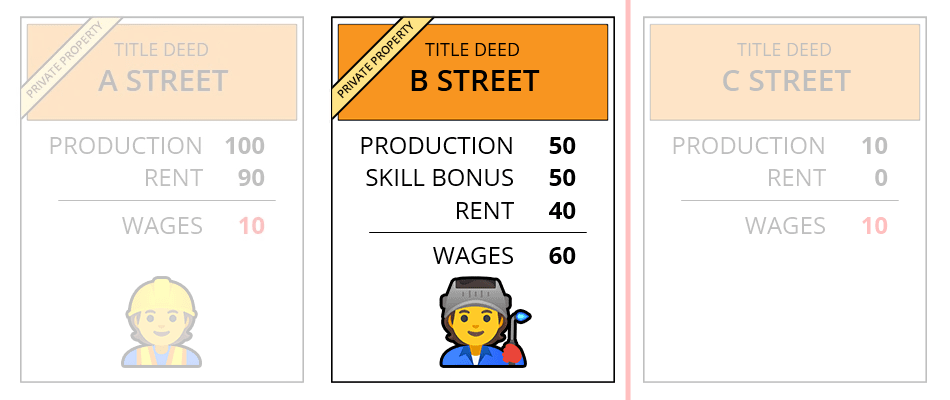

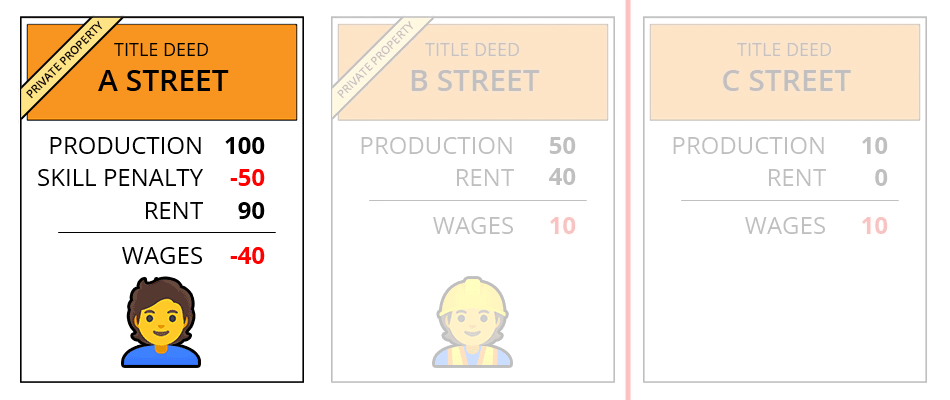

What if you’re less skilled than average? Let’s model what happens if you’re a young person just out of high school, with no formal training, higher education, or work experience, and therefore half as productive as an average worker. In that case, the best part of town is the last place you want to be:

While an above-average worker can outpace rent, you fall behind. Since the rental market is geared towards an average worker who earns twice as much as you, paying top shelf rent is a quick way to go broke.

Your best bet is to flee to the margin of production, the cheapest land available (or your parent’s basement), and take whatever job you can find. It’s not much, but at least you’ll be able to eke out a living:

In case you were wondering, if higher-income people start to move to your city, eventually they will drag the average productivity level upwards and rents along with it, gradually pricing out the local population. This is how gentrification works.

Now, does this mean rent is preordained to always go up, forever? Not at all. Rent only goes up so long as things like average productivity and population continue to grow. There are many forces that can reverse that. Unfortunately, many of them are bad.

One surefire way to lower rents is to just kill a bunch of people or drive them away. Rents in large cities famously crashed after the black plague, just as they did during the early days of the COVID pandemic. Crime, civil unrest, natural disasters, war, and plain ol’ economic decline all have the same effect, with varying degrees of permanence.

As productivity declines, so do absolute rents, and as population declines, so do landlords’ negotiating power, and with it the portion of production that goes to rent.

Fortunately, there are other ways to reduce rents that don’t involve literally or metaphorically bombing your own cities into submission. Things like frontiers. This brings us to the automobile.

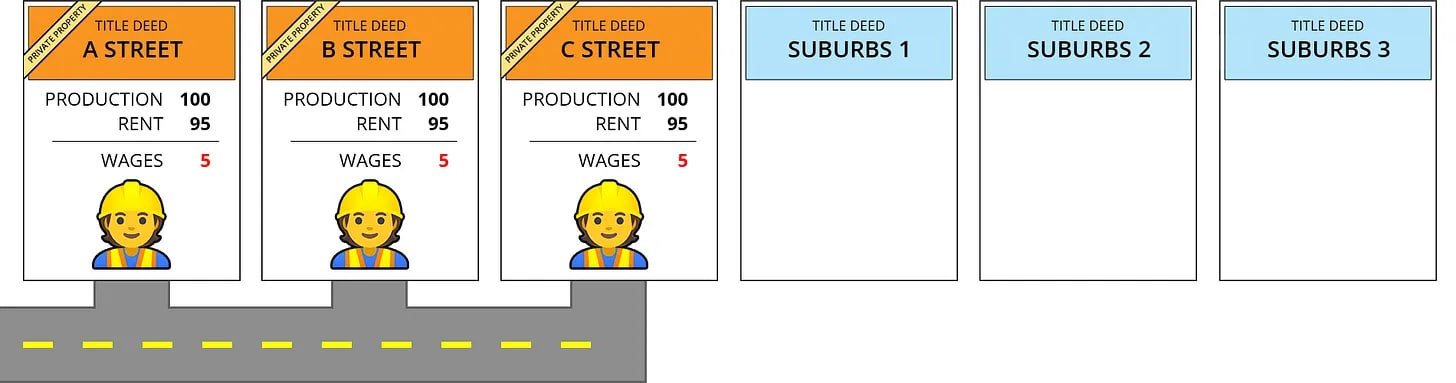

Let’s go back to our model from before, where all the best locations in the city are already in private hands and workers are squeezed to the limit, which was the situation at the height of the Gilded age, the time in which Henry George was writing.

What if we invent the automobile, build out highways, and juice homeownership through generous subsidies, and programs like federally-backed mortgages and mortgage interest rate deductions? This opens up a massive amount of suburban land for development, effectively duct-taping a third Monopoly board onto our original two game boards. As automobile expansion connects the city together, but before it reaches the suburbs, the model changes to this:

Access to the best jobs in the city is no longer gated by how far you can walk, so lots A, B, and C are now equally productive. However, this increase in productivity does workers no good because they are all still in perfect competition with each other for locations, and all residential land in the city is monopolized. This means landlords can charge as much as workers are physically able to bear. If a tenant doesn’t like it, there is another willing to take their place. It’s not like they have somewhere else to go.

The next day the suburbs open up, and suddenly there is somewhere else to go.

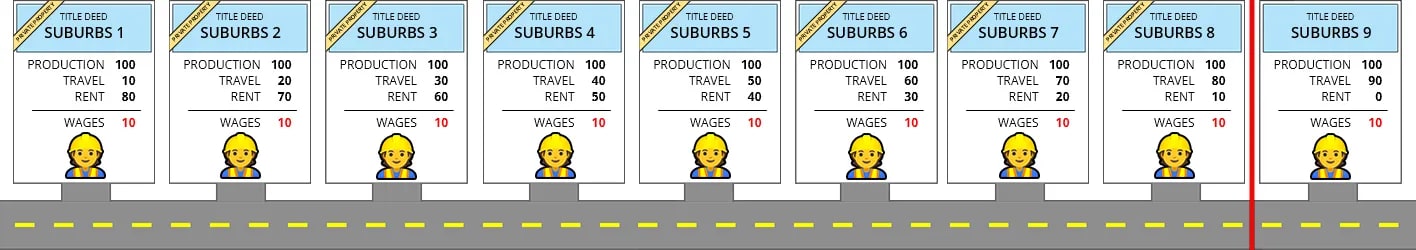

The suburbs are just as productive as downtown, because the automobile grants access to the same high-paying jobs. The difference is time and money spent commuting, a cost we’ll subtract from production along with rent to calculate effective wages. What is the effect of simply having the option to move to the suburbs?

Rent plummets:

Suburbs 1 is now the best rent-free location, marking the margin of production. A worker can simply move out here and pay a little more in commuting costs and be left with 90 units in wages, leaving the landlords with no choice but to match that offer.

Opening a new frontier is a fantastic trick if you can pull it off—except of course for all the people explicitly excluded from it.

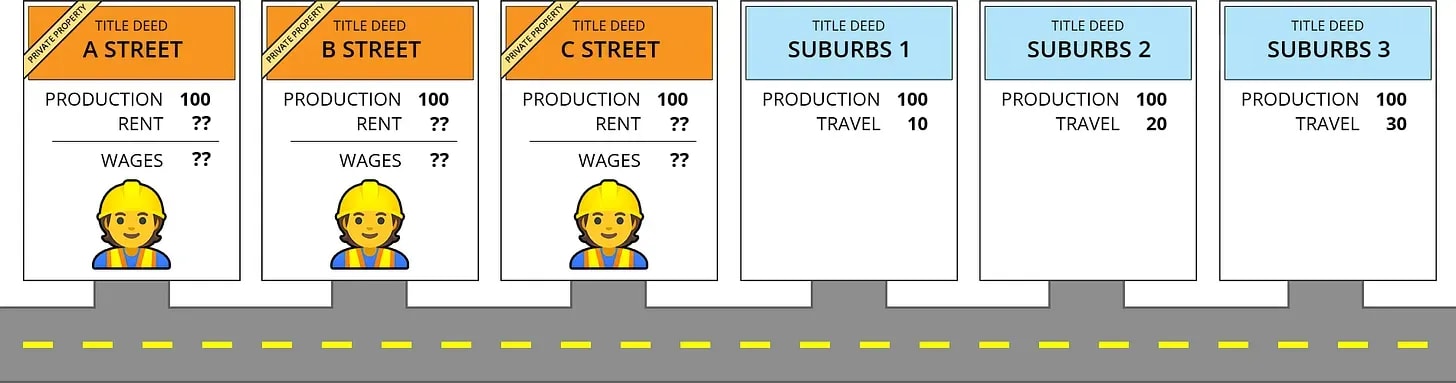

Frontiers also don’t last forever. Steadily the land gets bought up, either by landlords renting them out, or by workers becoming owner-occupiers. This extends the margin of production outward notch by notch notch, and with it the amount landlords can charge in rent, as the next best alternative steadily gets worse.

Eventually we will reach the end of our expanded frontier. But can’t we just keep going, and outrun the margin of production? We built a few suburbs, can’t we sprawl out even further and keep making more?

Let’s give it a try! As we keep building out suburbs and steadily filling them up we’ll eventually arrive at a scenario like this:

Even if everyone has access to the same average paying job, the cost of travel, in terms of money-dollars, time-dollars, and pain-in-the-butt-dollars, keeps rising as you go further out, lowering the effective value of the far flung locations. As each location gets bought up, the margin of production pushes out further.

At some point a job in the city is no longer worth the cost of super-commuting, and the marginal worker gives up and moves out of the area. This puts a natural limit on how far we can sprawl our way out of a housing crisis.

Many people, especially in the wake of the COVID pandemic, speculated that telecommuting and the rise of remote work would open a near-infinite frontier, and thus save us from the problem of locational scarcity. It’s basically like teleportation, right? You can live anywhere, but still have access to your high paying job in the big city?

Unfortunately, things didn’t pan the way people expected. The actual immediate effect of remote work was to increase the price of housing. Tech workers moved into bedroom communities across the country, particularly in sunbelt states like Texas, buying up property that was cheap for them. As people with high paying remote jobs moved into town, they raised local demand for housing as well as the earnings potential of those living in the area, and thus housing prices and land rents.

Frontier expansion is a trick you can’t keep doing forever, and as scarcity sets in society begins to boil over with tensions not just between classes, but between generations. Baby boomers, Gen X, Millennials, and Gen Z have each had their turn at the Monopoly board, with the older generations making out the best of all. As Generation Alpha knocks at the door, how will they carve out their own piece of the American dream if their only choice is to buy it at ever-inflating prices from those who came before?

As Herb Stein famously put it, “If something cannot go on forever, it will stop.”

We have reached the end of America’s frontiers, and now the only question is what sort of end we shall face. We must either change the rules to the rigged game, or else roll the dice and discover whether the next generation will peacefully accept being crushed beneath them.

By George, Land Value Tax would fix this.

.png)