The High Cost of Letting Accountability Expire with a Role Change

On my last deployment to Afghanistan — near the end of the war — I worked under a group of mid-level leaders determined to leave their mark. What we needed was introspection: A hard look at our own ineffective practices and a deeper understanding of the environment in which we operated. Instead, the mid-level leaders decided to cut over a million dollars from our budget, mostly from our capacity to collect survey data from local populations.

On paper, it looked like a victory. Executive leadership for that rotation praised the move as a cost-saving success for the taxpayers. We were sent home as fiscal heroes. Both mid-level leaders responsible for the decision were later promoted into senior leadership and given new roles.

Nearly a year later, I spoke with a member of the team that replaced us. What I learned was sobering: The budget cuts had gutted their ability to carry out certain aspects of their mission, and not just for their team, but every team that followed. Executive leaders in the following teams were furious, claiming the cuts had exceeded the previous leaders’ scope of authority and that they had crippled future operations. But by then, the money was gone, and in military budgets, once you give up funds, you don’t get them back.

The operational capacity of every team that came after us had been compromised. Yet no one was held accountable, and the two leaders went on to gain even more responsibility. When I later brought this up to one of these leaders, hoping at least for reflection, they doubled down. They called it “the leading edge of innovation” and insisted I should be proud to have been part of it. I walked away from the conversation frustrated and empty.

What haunted me wasn’t just the decision those two mid-level leaders made. It was how easily they walked away from it. Not just in the moment, but forever.

Promoted. Celebrated. Untouched.

Meanwhile, the damage they caused became everyone else’s daily reality for several years to come. There was no audit, no reckoning. No one cared. Our own executive leaders back home seemed to perform just a quiet, collective shrug as the consequences settled on the backs of the next team. And the next.

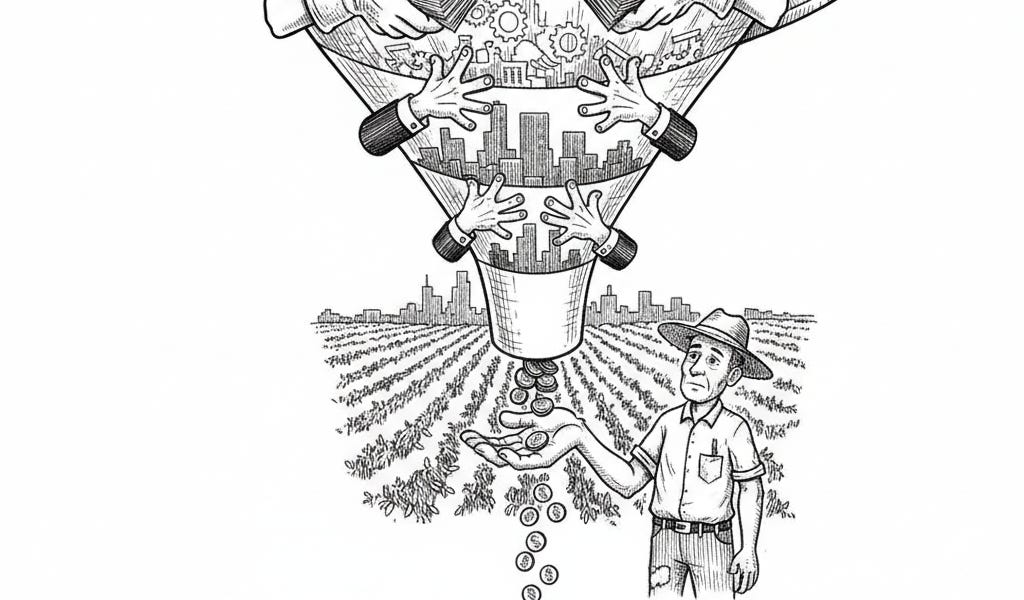

This isn’t rare. In far too many organizations, leadership accountability has an expiration date: Once the title changes, the past becomes someone else’s problem and the leader who made the bad decision escapes all the consequences.

I’ve come to learn that the system rewards clean exits, not clean outcomes. And the wreckage to the people? To the team? To the next leader and their capacity? It becomes institutional baggage.

Unclaimed, unspoken, and quietly corrosive. It spirals into impersonal mantras like, “Do more with less” or “If they can’t hack it, they need to find another job.”

Let’s talk about why this happens and what we can do about it.

If you have ever joined a team with a bad culture but with a good leader, and wondered how that happened, it is because someone created it, the organization didn’t fix it, and then expected new leaders to manage the negative consequences alone, as if they caused it themselves. Often, seasoned members of the team know exactly what happened and who is responsible for it, but are powerless to change it. Culture eating strategy for breakfast and all that.

I wrote about one of the reasons the bad leader is allowed to create negative consequences for others without any blowback for themselves. That is, their social credibility shields them from such blowback. But the problem is more complicated than being in a clique.

The larger problem is how our brains use time to either reinforce or stop behaviors. This is obviously true with parenting, but the necessity of an immediate connection between behavior and consequences does not stop when we become adults. And it goes in multiple ways, both for our own consequences and how we view others should receive them. Once enough time has passed, we stop making the connection between the behavior — or the person performing it — and the consequences of that behavior.

And if the aftermath of a bad decision occurs after the person has left the role, it becomes nearly impossible to associate the bad decision with the person who made it. After all, if we didn’t see the person make the decision immediately before everything came crashing down, were they really responsible for the wreckage? Our brains don’t think so.

We see this fallacy in politics all the time: One party makes decisions about the an issue during their term in office. Then the other party gets elected, but the blowback from the decisions made in the previous term occurs while the new party is in office. Then it becomes a blame scramble, where pundits attempt to make connections where there were none, or ignore the connections where they actually exist.

As much as everyone hates politics, it isn’t politics that creates this problem. In a sense, we create an “out of sight, out of mind” inconsistency in which the people who currently own the problem are also responsible for solving it. In some cases, they get blamed for creating it, or even judged by their ability, or inability, to solve a problem someone else created. In this case, the organization fails the new leader by throwing them in a hole, tossing them a shovel, and telling them to dig themselves out of it.

To make matters worse, these new teams who have often experienced decreased resources, damaged morale, burnout, and broken relationships are also judged by their ability to “pull themselves up by their own bootstraps.” They are unfairly expected to solve a problem they didn’t create at the same time they are required to accomplish their own objectives… typically without organizational support.

So, the team with a new leader starts at a disadvantage. The new leader has to learn to swim in unfamiliar waters with sharks already out for blood. And the organization either fails or refuses to hold the previous leader accountable for the wreckage they caused.

Even if the promoted leader is not being shielded from consequences, there is literally no functional difference between the organization actively protecting a bad leader and the organization remaining indifferent to the consequences of the bad decisions made by that leader during their tenure. In this case, indifference is all the protection a bad leader needs.

The system — or if you prefer, The System — has a habit of being the real villain behind the indifference, protecting those who victimize others, and covering up the wreckage of bad leadership by sweeping it under the rug.

This happens because leaders allow it to happen and have created — actively — a culture that fails to hold their leaders accountable to the decisions. Here are some symptoms of such a culture

- Lack of open conversations about how decisions are made or who they affect

- Non-competitive or automatic promotions on a regular basis

- Those in power allowed to “punch below their weight class”

- Inability of senior leaders to accept criticism from their employees

- Lack of processes for employees to voice their concerns

- Poor professional development for leaders

- Performative feedback is allowed (e.g. only once a year) or no feedback

- Hiring or promoting for “culture fit” rather than with validated practices

- Bad leaders (or those who know the right people) fail upward, while critics, high performers, and those who are not well-connected stagnate

Too often leaders and the HR departments that support (or cover for) them view feedback about leaders as unproductive negativity. For example, have you ever heard leaders hush employees who complain about a manager who is bad for the team because it “drags everyone down” when team members file complaints about poor leadership practices?

It’s true what they say in politics that the cover-up is often worse than the crime. But, in this case the cover-up often reveals an ongoing culture or system that runs deeper and has damaged more people than a single offense. What’s worse, leaders will let the culture continue, which will create and leave wreckage for years to come.

When I was in the Army, I would occasionally hear about a very senior leader fired for some kind of egregious behavior. This behavior could range from sexual harassment to toxic leadership to normal corruption. My first thought, every single time: This should have happened sooner, probably decades ago.

Literally no one, after a decade of even mediocre but non-destructive leadership wakes up in the morning to say, “I’m going to be a toxic leader for the rest of my career” or “I’ve gone 20 years with a perfect record and I’m going to mess it up by making a sexual comment to someone today.” The problem — and this isn’t merely a problem within the military — is there is little accountability for leaders after they leave a role.

Here are some ways to improve accountability in any organization. Note that probably none of these ideas are common and all of these ideas would require a significant amount of leadership backing to enforce.

- Key decisions and their anticipated effects are tracked by name, not just the department or the role.

- All leadership transitions include either individual interviews or focus groups with the promoted leader’s former team, with a promise of anonymity for any response.

- For a leader with multiple promotions within the same organization, metadata of transition reviews should be made available to promoting authorities.

- Attrition levels are measured by time, leader, and department; then compared against peers or leaders with similar roles or in similar departments

- Anonymous, multi-source feedback should be reviewed by neutral third parties

- Leadership promotions should include a delay period — or be provisional — to assess the impact of key decisions made in the prior role, before the promotion becomes permanent.

- Promotions for all leaders are on a provisional basis, until the results of major decisions they made within their departments have matured.

- Implement 360-degree reviews, or multi-source reviews, with the results going to disinterested parties.

- Finally, for any leader under consideration for promotion, the team they lead should be given a vote or some voice in the decision. Anonymously.

Accountability shouldn’t expire when a title changes. It should follow the decisions, the impact, and the legacy left behind. If we want to build organizations where leadership actually means something, beyond optics and upward mobility, then we need systems that remember.

This isn’t to punish the past, but to protect the future. Because the cost of indifference isn’t just broken teams. It’s broken trust.

Broken people.

And eventually, a broken organization.

.png)